Editor’s Note: As this Yussef Cole interview with David Wolinsky reveals, the worlds of gaming and motion design have a lot in common. From aesthetic concerns to labor issues, there’s much to be learned from conversations like this one. Enjoy.

As someone who shares an equal fascination with motion graphics and the ever-burgeoning cultural totem that is video games, I figured that I would have a lot to talk about with freelance writer and journalist, David Wolinsky.

Thankfully, I was proven right.

Wolinsky’s latest effort, Don’t Die, is an interview series that orbits the subject of video games while covering a wide range of issues that also happen to affect those of us working in motion graphics and visual effects.

Don’t Die: An interview series about surviving videogames

While the kind of work being done in gaming and motion design differs significantly, the kinds of discussions you might engage in after work over drinks bear striking similarities: Artistic integrity, work-life balance, diversity, getting paid, These are all well-trodden topics regardless of whether you’re a level designer working for Electronic Arts, a traditional animator working at Buck, or a Nuke compositor working at The Mill or Blacklist.

Interview with David Wolinsky of Don’t Die

Many of the folks who view Motionographer as their window into the work and lifestyles of creative professionals know very little about video games and even less about the industry that supports them.

I think the distant cousins of gaming and motion design can be brought closer together and mutually improved through conversation.

I think the distant cousins that these disparate fields appear to be can be brought closer together and mutually improved through conversation. My hope in conducting this interview is to expand the personal context of these discussions.

This is partially what David Wolinsky has been attempting to do with Don’t Die: releasing the video game industry from its fortress of solitude and promoting the sharing of information and experience with as many other fields and disciplines that he can find.

A wandering path into games

Wolinsky has always been a writer in some form, but he wasn’t always writing about video games. His focus early in his career was on the music business:

I always describe myself as having a broader entertainment journalism background. I realize now, 10 years out after college, where I studied music business — that’s sort of where my fascination with what I like to call the “less sexy behind the scenes” sort of stuff began.

In the last 10 years, I’ve gone from being an editor at The Onion, to helping start their game section while I was there — it was not something I was hired to do, that was just an additional project I spearheaded.

So that’s sort of my start as an entertainment journalist. I was also city editor at The Onion, and I was an editor at NBC where I had the distinction of helping start, and then shutting down a small business blog. I’ve done some curriculum building for a couple of universities and their game design programs. I’ve also done curriculum building and teaching at Second City.

I’m just sort of fascinated by all things pop culture. If you had talked to me a couple of years ago, you would have been talking to me about my interviews about comedians.

Wolinsky’s primary aim in starting Don’t Die was to capture some of the nuance that wasn’t evident in many of the online conversations about video games.

I’ve always run into this thing with the game industry where there’s very little cooperation when you want to go off script.

There’s an example that I often think of: The year that I started Don’t Die, I went on a studio visit and another writer asked whether there would be a day/night cycle in this particular open world game.

There was a PR person there, and they’re very careful, very guided — which is not inherently bad, but you run into stuff like asking if this game is gonna have days and nights in it, and the PR person swoops in and says, “We’re not answering that question.”

That’s a very innocuous example of a bigger systemic thing going on, which is something that didn’t really crystallize for me until I was doing Don’t Die for about a year, having logged 130-some interviews. I just get this sense that the games industry is afraid of its own audience, unsure of how to trust it with information. And this is a really roundabout way of saying it took tempers being so high to realize that there’s just a lot of distrust going on.

That was sort of Don’t Die’s starting point. We obviously are a year and a half away from that summer, and just as I’ve done more and more interviews, the questions have gotten bigger. My questions don’t really have answers, but for some reason I have that skill of just listening and making people feel safe to open up and to feel trusted to share.

On a broader level, what I’m exploring is: How creative industries in general are kind of broken, or how they’re making people not feel heard. Whether it’s someone in the audience or a CEO who placed themselves in self-imposed exile from the press — or people from other industries who have interesting parallels.

Anyone who’s worked under a non-disclosure agreement can understand the kind of politics and frustrations at play here.

I just get this sense that the games industry is afraid of its own audience, unsure of how to trust it with information.

It’s natural for companies to want to protect their ideas against misinterpretation or outright theft. It’s just as natural for employees, especially those employed in the creative industries — who naturally take pride in and want to share their work — to feel constrained by the enforced secrecy around some higher profile projects.

A lot of the frustration comes down to feelings of unfairness and power-imbalance. Who holds the cards? Who is making the profits while other companies struggle and fold?

This came to a head in the discussions around feature film VFX leading up to the 2013 Oscars – when Rhythm and Hues won an award for Life of Pi right as their company was collapsing.

Labor issues and unionization

A major through-line of Wolinsky’s work is labor issues as they relate to video games.

Many of the people he interviews talk about “crunch” and the obscene number of hours they are often required to commit, often at the expense of their personal lives. I find ample ground for comparison here, not only in the world of VFX, but in motion graphics as well.

I asked David about a recurring idea in his interviews that you, as a creative worker, should feel lucky to be there and shouldn’t ask for anything more.

The economy has changed and gotten so weird since I graduated school. When I talk to people a couple years out of school now, the attitude seems to be that they’ll happily pay someone for a job. It’s very bad.

Unionization in games — that’s something I’m working on an article for right now — is such a confusing thing because people really want to compare video games to Hollywood. While on the surface that seems to be a logical comparison, when you start digging into the details, Hollywood is one of the strangest trajectories and workflows to imitate because it’s so stacked against the creator.

These conversations have been happening for decades, it’s just weird that it took about a year and a half ago in video games for that conversation to start happening. But the point is, that could have been a solvable problem. That could have been a thing that was addressed.

The video games industry likes to say it’s bigger than Hollywood, but they forget to say they’re adhering to all the lamest parts of Hollywood. It should hold itself up as better.

Getting into the game

As massive as the games industry is, the path to employment often appears quite narrow.

I’ve always been frustrated by the lack of a bridge between motion graphics and video games, even though they are both driven by visual design.

Specimen is a simple but addictive game that challenges players to match colors

Of course, there are some success stories, like Motionographer’s own Erica Gorochow and her recent iOS game Specimen. Also of note is the scripting tool Squall being developed by Marcus Eckert that should allow After Effects animation to transition seamlessly to a mobile development environment.

But by and large, the leap from motion graphics to games still seems rather impossible. I asked David how one might get involved in the space of video games.

Although [games] is a passion industry, there’s no point of entry unless you have certain skills, and then it gets a little bit easier.

I think that’s why you see the trajectory for a lot of writers in the space has been to go work in PR or communications or community management. They don’t let you near the games. I don’t think that’s nefarious or anything. It’s just a fact. It’s a sign of our economy, that you need to diversify your skill set.

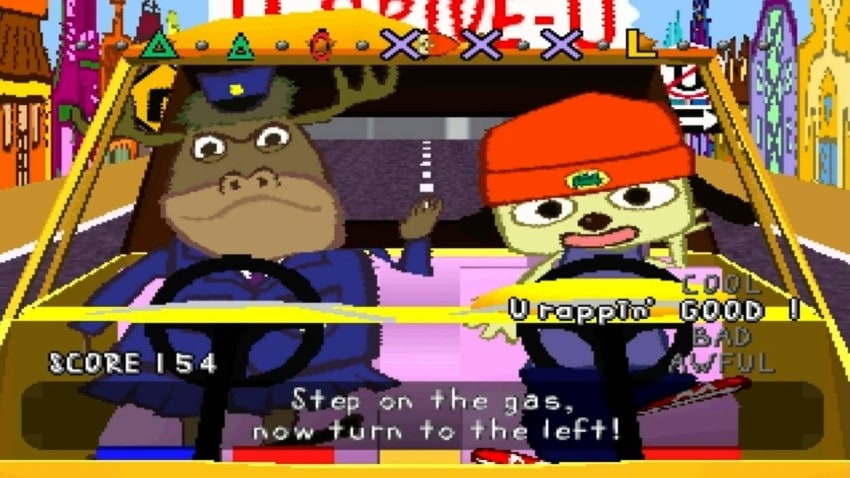

PaRappa the Rapper was a rhythm game created for the original Playstation console

But I did an interview late last year with Rodney Greenblat, who was the co-creator of Parappa the Rapper and Um Jammer Lammy. He was just a regular ‘artist’ artist, like a visual artist. He had an exhibit I think at The Whitney, and that exhibit happened to get noticed by someone who was connected with Sony in Japan.

He ended up getting a job at Sony making stuff like keychains, advertising projects unrelated to their games department. But then this project came up, and he was invited to collaborate with what would be considered a huge team then, about twelve people.

I asked him: “If you’re a person who’s an artist or you have a different discipline and you want to work in the games industry, what do say to you college kids when they ask, “How do I do what you did?”

And he said, “I don’t know.”

Because he just got lucky. There is no way.

I’ve had that sort of career myself, where you just fall into things and you can’t intentionally make them happen.

Artistic integrity and/or customer demands

Happiness and job satisfaction are nebulous goals. Not being creatively satisfied is a complaint often heard from folks in the motion graphics industry. It’s why people start up side projects at home, or leave larger companies to start smaller ones.

I asked David to dive a little deeper into this tension between artistic integrity and satisfying the client.

I think a lot of it depends on personal temperament. Some people may find some work incredibly rewarding while others find it to be an incredible waste of time.

People like to pretend that client work can exist without artistic integrity — or vice versa. Yeah, you can go strictly one direction or the other, but there’s more of a connection than I think people let on.

Many fans were upset over the ending of the Mass Effect trilogy

There was an interview I did early on with Greg Zeschuk, who’s sometimes referred to as one of the “Doctors” at Bioware. He was involved with the Mass Effect trilogy.

I remember — I’m sure you remember too — the ending for the trilogy. A lot of people in the audience were really upset about it. They demanded a new ending, because they felt like what the company had made wasn’t good enough.

And, as I’m sure you remember, the company relented and made a new ending to appease their audience. I asked Greg about it. I came at it from a couple of different directions to get a sense of like, did he feel this was kind of ridiculous? Did he feel this was ok?

And although Greg has left the game industry, I do sort of wonder about the answer he gave: He felt his responsibility and the company’s responsibility was as commercial artists. It’s their job as artists to please the audience.

And I guess for me that opens up: Well, what is the statute of limitations? Should [Capcom] go back and change Ken from the original Street Fighter because a lot of people didn’t like him?

Whether you’re a creator working for a contractor or yourself, if you’re making something for a nebulous blob of people, you should pay attention to what people are saying and consider it. But if you bow to what everyone says, then it stops being the thing that you created, and you’ve entered into this weird contract where you’re working for your audience.

Looking outside the industry for growth

Expanding one’s viewpoint beyond what is comfortable or familiar can be challenging — but also tremendously rewarding. Narrow-mindedness in any industry leads inevitably to stagnation.

That’s why when looking for inspiration, it helps to study painting or photography instead of last week’s trend. That’s why, when looking at labor issues, we should take lessons from the downsides of the sharing economy or the history of unions in Hollywood. There is only so much you can grow if you only look inwardly at the familiar for lessons.

David Wolinsky’s approach in writing about the games industry is meant to take a multi-disciplinary look at a field that is normally dominated by narrow perspectives. The discourse around games is improved when disparate views are allowed into the discussion.

In conducting this interview, I hope to carry forward the spirit of his work into our own discussions regarding motion graphics and visual effects.

David Wolinsky is on Patreon, so if you’d like to support his writing you can do so here: patreon.com/davidwolinsky?ty=h