For those of you who haven’t seen Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj on Netflix, I highly recommend that you stop what you are doing and check it out this instant!

The show is insightful, funny, and informative. At a time when political commentary is at an all-time high, what sets Patriot Act apart is how topical each episode is as well as its production value.

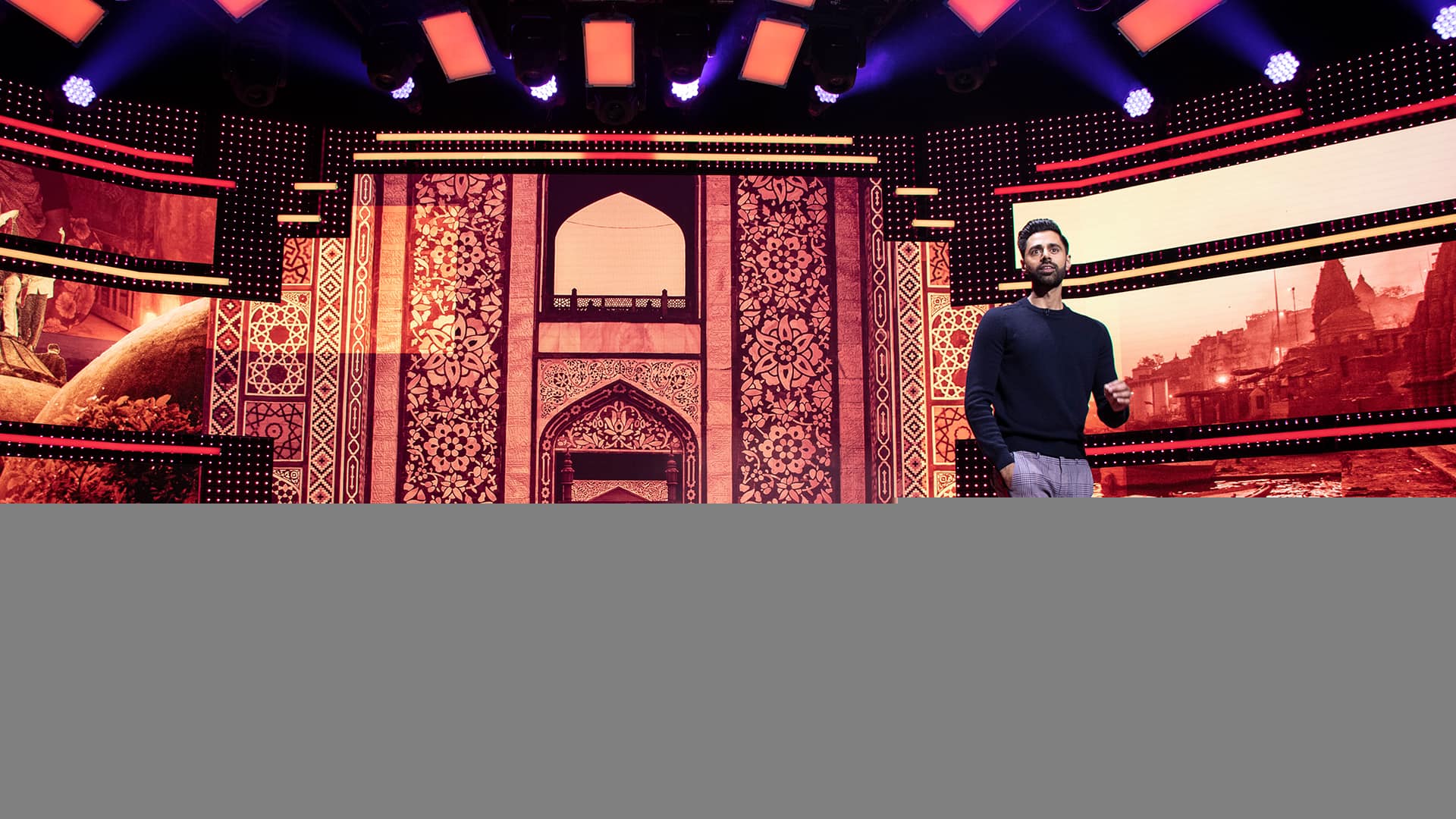

We’ve all seen the typical nightly show with a host sitting at a desk and over-the-shoulder graphics. Patriot Act does not follow this formula and immerses not only the viewer, but Hasan himself, in a world of supporting visuals. It’s amazingly done and acts as a perfect example of motion design supporting a narrative and functioning as more than just a 16:9 rectangle or yet another advertisement.

The following is a conversation with the show’s design and animation team:

Michelle Higa Fox, Jorge Peschiera, Justine Webster, and Yussef Cole.

Enjoy!

First of all congrats on the amazing work on Patriot Act and the recent Peabody Award! The show is amazing and deserving of all the praise.

To start, can you each tell us a bit about who you are and the work you’ve been doing on the show?

MHF: I’m Michelle Higa Fox, founder and Executive Creative Director of Slanted Studios, where I specialize in combining high-end motion graphics with non-traditional screens. I directed the graphics for the pilot, shepherded the pipeline and staffing of the graphics and previz departments as we scaled to show, and served as Creative Director for the inaugural season of Patriot Act.

JP: I’m Jorge Peschiera and I was brought in as the Design Director for the first season and took over as Creative Director as the second season ramped up. Prior to this, I worked as Creative Director at Thornberg & Forester and then Trollbäck + Co., as well as freelance stints at loyalkaspar, Sibling Rivalry, and a few others. Aside from managing the team and supervising/co-directing each episode, a key part of my role is to steer the show’s long term aesthetic evolution. We see the show’s look as something that can be re-shaped and refined collaboratively over time.

JW: I’m Justine Webster, GFX Producer, and I joined the team just a couple weeks before we taped episode 201. Prior to working here, I was a producer at an ad agency, and before that I taught English as another language to immigrants and refugees at community colleges in Seattle and managed programs for international students. Can you tell I like change? At Patriot Act, I manage our team of designer/animators along with Jorge, facilitate communication across departments, manage our workflow and make improvements to our process, and do my best to play to each of our team member’s strengths.

YC: My name is Yussef Cole. I’m the Head of Animation at Patriot Act. Along with the design director, I directly oversee the graphics team. I also help execute Jorge’s overarching design goals for the series. I oversee the animation templates that the team uses and am the point person for dealing with the video system operators who put our graphics up on the stage.

How did each of your involvements come about on the show?

MHF: I was approached by Hasan and his team in August of 2017 to create a proof of concept for a new type of tv show — a way to talk about politics and culture that wasn’t a suit behind a desk or a man roaming the streets abroad. Working with Jen Vance, Erica Gorochow, and FirstMates, we were able to turn around a pilot that showcased the potential of tightly interwoven performance and motion graphics. From there, it was a relatively fast whirlwind of growing that idea into an awesome crew capable of cranking out episode after episode on a weekly basis.

JP: Michelle approached me in June of 2018, while I wrapping up some projects at Sibling Rivalry. She told me about the show concept in a phone interview — it sounded amazing — and asked me and a few others to submit a motion test and treatment. I then had an interview with the show’s senior staff and a second one with Hasan. They all turned out to be lovely people, so I was happy to get the offer.

YC: Michelle hit me up, as she had worked on the pilot episode for Patriot Act a year earlier and had been asked to return as creative director. We’ve worked together a bunch, and trust each other implicitly so I knew that if she was signing on, then this would be a project worth getting involved with.

JW: Jorge Peschiera and I worked together on a graphics project for Microsoft a couple of years ago. I was flattered to get an email from Patriot Act saying he had put my name forward for the GFX Producer role. I was really excited by the opportunity to merge my love of design and storytelling with issues that matter to me. When I joined, I identified process and communication areas that could be improved, and worked to do just that.

What were the early conversations around what the show could be and how motion design could play a role?

MHF: From the beginning, Hasan and Prashanth wanted to create a visual podcast — what happens when you take RadioLab and cross it with a Beyoncé concert, take a TED Talk and give it the Michael Bay treatment.

The entire design of the show was meant to support the central tenet of providing context, not distraction. We were all conscious of the fact that there were no other correspondents or guests for Hasan to throw to — the screen was his co-host. It needed to flexibly elevate both his informational and emotional points, not just be a visual punchline.

YC: There were a ton of ideas and looks for the show before the show runners settled on a direction. There was talk of an interactive stage that responded to Hasan’s movements, as well as a more “expensive” 3D, C4D Octane-driven look. But thankfully, we settled on a slick, yet ultimately far more workably minimal style, the early design of which was spearheaded by the incredible Erica Gorochow.

JP: Feasibility was a big question early on. At my first interview, our showrunner Jim asked me “So Jorge, do you think this is even possible from a production standpoint?” And I said something like “I’m not sure, but I think it would be fun to find out.” We have to design for speed and volume—we crank out an entire 24-minute show sometimes in just 3-4 days, even as it’s being rewritten. Sounds crazy even now that we’ve done it.

One thing that I find so successful about the show is that it’s taking a fairly common structure, talking personality with over-the-shoulder graphics, and turning it completely on its head. How did you all land at the final format with the fully immersive set, and were there any other options on the table?

MHF: From the very first meeting, Hasan and Prashanth knew they didn’t want the typical suit behind a desk, skyline in the background, graphics isolated to the corner, and they saw the potential of how the stage and graphics could be more fully integrated into the story.

You could see the beginning of that integration in Hasan’s Netflix special, Homecoming King. Mark Janowicz, who designed the lighting and LED sets for Homecoming King, the proof of concept and Patriot Act, was essential for achieving that vision. It was important that the set had a sculptural signature of its own and didn’t just feel like a single projector screen.

Once we had the set design, we were also very adamant about the stage staying true to the real space that Hasan was interacting with physically. Even though wonderful camera-tracking technology like NCAM exists, if everything took place on a virtual set, we might as well have shot it on greenscreen. And for a show that was all about live performance, audience reaction, context, and interplay between the host and the data, greenscreen would not have been appropriate. The whole crux of the show is the screen acting as an extension of Hasan’s mind and both him and the audience being able to experience that in real-time.

YC: This was something that I largely credit to Hasan. He wanted to find a way to make his show stand out, to set himself apart from the late night talk show crowd. He’s got a great sense of style and a solid grasp on technology, so he was the driving force behind making Patriot Act a show unlike anything else on TV.

Conceptually, the topics are very in-depth, how involved is the design and animation team in conceiving of the visuals and how they will aid the story?

JP: The stories always come first, but the process of visualizing is pretty collaborative. Prior to receiving the first script, we’ll have a meeting with the News, Writing, and Archival teams, where we talk through the main chapters of the story, ask questions, propose ideas. We then start sharing visual reference, sketches, and/or storyboards for some of the bigger moments with News and Writing, as well as collaborating with the Archival team to build our background collages for the episode. That initial creative exchange ends up shaping the graphic narrative, but our department gets a lot of leeway in terms of the aesthetic.

YC: It’s cool that we are encouraged to pitch our own ideas once we get a look at their script. The writers and the show runners are very receptive to new ideas, especially visual ones. A lot of them are used to the traditional comedy news show format of a small window over the host’s shoulder filled with graphics meant to resemble cheesy nightly news chyron, so it’s usually our job to come up with ways to take advantage of the massive canvas and dramatically different format we are working with.

JW: The whole process is extremely collaborative, both within the GFX team and between all the other departments. And, it really has to be because we move very quickly — clear communication and creative agility are necessities. It helps that everyone on our graphics team is incredibly supportive of one another, humble, and talented.

My first job was working at an ABC News station. One of the things I loved about that job was that it felt like I was equal parts journalist and creative. I imagine the feeling is similar on this show and you find yourself constantly learning about new topics. How has this affected your creative process and outlook on the role of motion design?

JP: Aside from the wonderful team I’m surrounded by, this is probably my favorite part of the job. I love diving into new subject matter with our amazing researchers, especially on international stories because you get to immerse yourself in new landscapes and visual traditions. We are tackling topics that might otherwise feel dry, or depressing, or confusing, but they are important for people to understand. A big part of our job as motion designers is to help clarify the confusion and present every topic in a way that’s unexpected and engaging. The nature of our show gives us a lot of creative freedom, but doing each topic justice and respecting the cultures we touch on is a responsibility we take seriously.

YC: This is one of the best things about working on the show. Every new episode is a wealth of knowledge to absorb and interact with. On top of that, we have the fascinating challenge of figuring out how to depict political events and figures in ways that no one else has thought of before. How do you present archival that doesn’t feel cheap or easy? How do you talk about Trump without plastering the screens with his face? What kind of imagery or design can make important, if dry, subjects like loan forgiveness and drug pricing seem interesting and exciting? Without fail, each new episode always brings a new unexpected creative puzzle to solve.

JW: I agree with everything Jorge and Yussef said! It feels very rewarding to work on a show that tackles such big, important issues but does so in an innovative and visually interesting way.

From a technical perspective, what is the process like during the development, design, and animation phases of each episode?

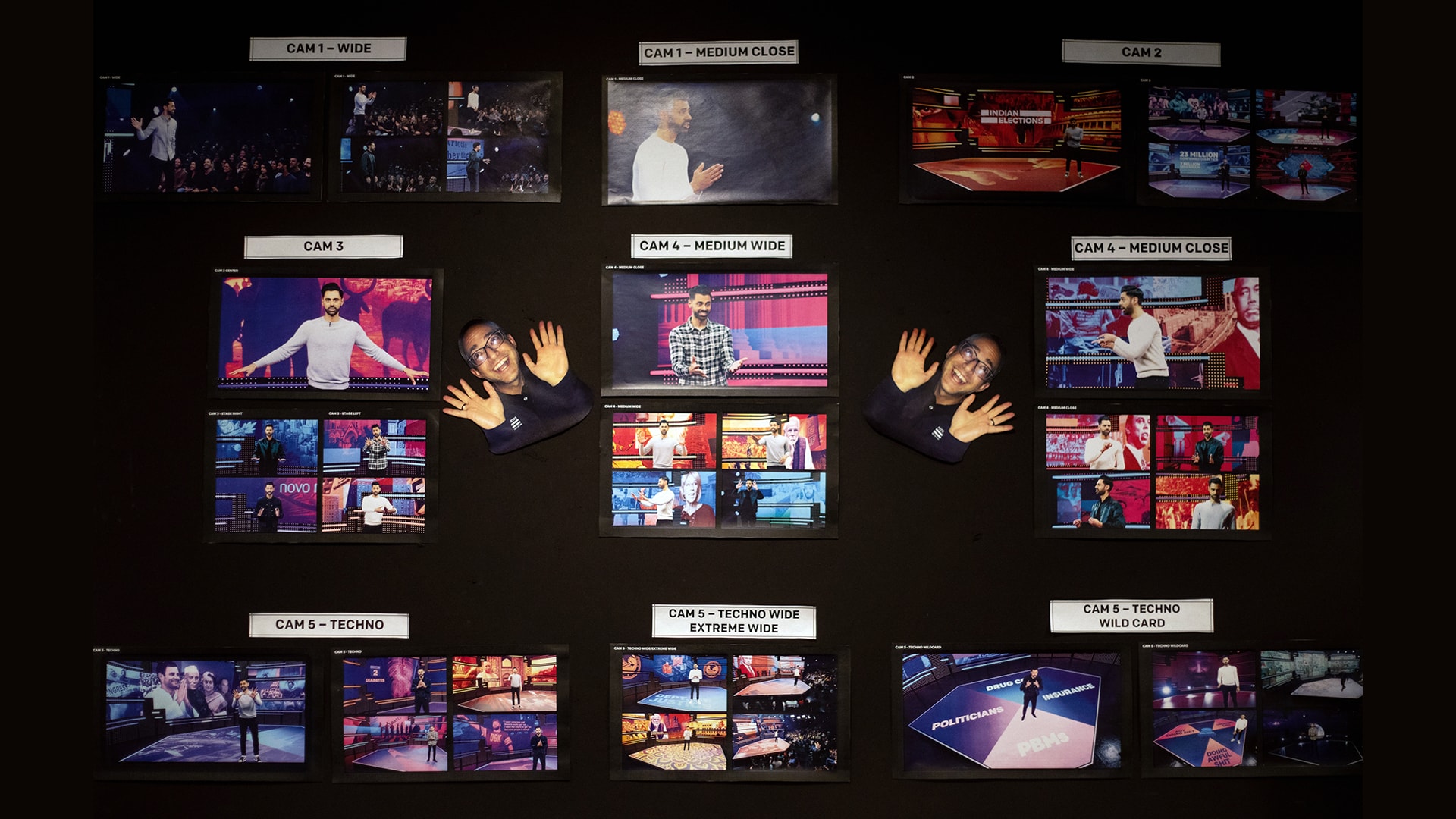

JP: Extreme modularity is a key component of this show. Because Hasan’s performance moves so quickly and scripts change constantly, elements must be built in bite size chunks that we can easily cut or re-order even minutes before we tape. We don’t always have time for discreet design/animation phases. Some pieces go from initial conversation, to final render in an hour. Our team is good at sharing tricks and techniques with each other. Coming up with ways to make the process stable and efficient is really where most of the innovation has been focused so far.

YC: We tape for six weeks and prep for another six. The period between taping is when we finesse our templates, figure out areas where the existing graphics can be improved and come up with new design ideas that we don’t get a chance to explore while we’re in the thick of it. Once taping starts, we usually have about a week to make all the elements for a full episode. During the lead up to taping, the team preps new elements and adapts existing ones to the script as it is updated. The day before taping, along with the director, the video system operators and much of the stage crew, we rehearse the latest version of the show on stage with Hasan. We address any additional changes early the following morning, make sure all elements are loaded into the video system and tested, and tape the episode that evening.

Similarly, I imagine working at this format is quite a bit different than your standard 16:9 workflow. What have been some of the ups and downs along the way?

YC: It’s a big learning curve to work quickly at the format that we use. The work area includes both the main screen and the floor, along with led strips and a giant led wall behind the screen that adds color and atmosphere. The comp is about 8k by 5k. Because our style is so minimal, with rare use of 2.5d or custom effects, and because the lengths of our renders tend to be fairly short, it isn’t as taxing on our computers as one might expect. You still have to be smart in how you design. We use 3D programs like cinema 4D extremely sparingly because 3D renders at the scale we need them tend to take a distressingly long time for our schedule.

JP: Perhaps an even tougher adjustment is keeping in mind that the graphics basically ARE the set, so we have to think both as motion designers and set designers. We have to think about camera angles, where Hasan will stand in the frame, how he will want to move. We have to consider how the placement of certain imagery can serve the story, and allow the cameras to reveal details as a chapter unfolds. We think about narrative flow; shifting the visual mood from one chapter of the story to another and identifying opportunities to surprise the viewer with an unexpected visual moment. This requires fluid, on-the-fly coordination between our team, the camera department, and Hasan.

How long does it take to produce each episode and what is the cutoff time before the show goes live and the visuals have to be finished?

JW: We work in cycles of about 12 weeks. Typically we have more time to work on episodes that fall earlier in the cycle, as we’ll have received those scripts earlier. That said, the scripts constantly evolve as the story unfolds, we learn new information or decide to shift the thesis of the story, something shifts due to a current event, etc. As we get closer to the end of a cycle, we usually have much less time, sometimes just 3-4 days from receiving a script to shooting. As for a cut off time, we are on call until the audience leaves! The vast majority of our elements are completed a couple hours before we tape, but the script is still evolving up until the literal last minute.

When it comes to Hasan’s performance and the flow of the show, are the visuals all pre-timed and he is working to hit specific marks or is it more of a modular process where the animations are being swapped in live?

YC: We build the show in such a way that everything can be reordered if the script changes last minute. Most of our assets aren’t longer than a few seconds long and can be called up, held, or looped. Often elements overlap, like a background that might stay up while foreground elements are laid over it. There is an assistant director who dictates where each cue comes in and goes out and a video system operator who follows the AD’s instruction over radio.

JP: Because the visuals are cued live, getting to know Hasan’s pace of delivery is crucial, and modularity enables that. We have to account for unexpected applause breaks, ad lib moments, etc. so most animation cues can only be a second or so long. That said, we definitely have experimented with more choreographed sequences between the graphics, the cameras and Hasan from time to time. Our plan is to pursue that more in future because I think they make for some of the best moments in the show.

The show has been very successful. I think it’s safe to say that a huge part of that is because of the creative approach to the storytelling. How do you see this evolving and what do you think is next for animation and design on Patriot Act?

JP: I’m glad you think so! There’s always work to be done in terms of process and polish, but a big goal is finding ways to create a more interesting flow between cues, a sense of being on a surprising, delightful journey through a topic. It’s a tricky one to solve, but one of the most exciting things about the show is that it really feels like it can keep evolving and improving — as Hasan likes to say, “I don’t see a ceiling.”

YC: Thanks to the nature of the format and the enthusiasm of the people working on the show it’s hard to picture a limit to the ways we can evolve and improve on the style of Patriot Act. Every new cycle (or season) brings a new set of innovations that we came up with during our off-weeks. This is owed to the dedication of the animators working in our department and the support of the show’s leadership, who absolutely get the need to continue innovating and bringing new visual ideas to the table. The screens are a really fun and engaging canvas that make you reconsider everything you thought you knew about motion graphics.

Finally, what’s next for each of you?

MHF: I’m loving seeing how the visual language of Patriot Act keeps evolving. Having been on the inside, it’s amazing to tune in as a viewer and see the show achieving visuals we had only dreamed of in season one. I’m hoping the show provides an inspiration for more creators to use motion graphics in new and varied contexts.

JP: Personally, I’d like to keep working at evolving and improving the show, at least until I can see a creative ceiling, which seems far off. I really feel lucky that I get to be here, surrounded by such great people every day and working on a show whose perspective I really believe in.

JW: I feel the same way. I’m excited to keep facilitating communication, improving our systems, and smoothing the path forward for our team so we can continue to evolve and improve our approach to visual storytelling.

YC: Patriot Act is one of those rare cases where the job is creatively compelling and feels ethically on-point. The politics of the world seem to get worse and worse, so it’s a small comfort, at least, that I get to work on something where everyone involved just wants to spread information, educate people, and make people laugh, not sell them a product. To be honest it’s hard to envision going back to the commercial world. So I plan to be on this train for as long as they’ll let me ride it.