Filipe Carvalho has collaborated with a number of leading studios and networks over the years, including Digital Kitchen, Sarofsky, Blur, HBO and FX, working on such properties as Cosmos, Spiderman and Thor.

In anticipation of an upcoming Google documentary detailing the process behind the Semi Permanent festival opener, we reached out to learn a little more about Filipe’s life and work.

Q&A with title designer Filipe Carvalho

You started out as a web designer. How and why did you make the transition to a designer for broadcast and film?

I started as a web designer doing layouts for corporations and real estate agencies, but when Flash came around and started to have more and more coding, I started to see where things were going. I thought about moving towards my real love: film.

While still a creative director for the web, I started to develop my own motion design skills, learning as much as I could, trying to build a decent rookie portfolio.

I decided to send an email to Digital Kitchen and try my luck. This was around 2009. They got back to me, and I started on a project. I was in.

I think I know the answer to this one but how would you describe your style?

Cinematic. That’s what people tell me anyway. I wear my influences on my sleeve. I’m drawn to photographic work, elegant type and subdued moods.

I also really believe in the “less is more” mantra. I try to do that in my work and that makes me stand out from the crowd sometimes.

But for me the most important thing is concept. Concept first. If you don’t have an idea, no imagery in the world is going to save you.

You work directly from Portugal. How do you deal with working across time zones?

I’m based in Lisbon, Portugal. That’s at least a 5-hour timezone difference from the US. I actually have a daytime job; I’m a designer at a production company in Lisbon. That means I only work at night and on weekends for US clients.

So a normal day for me is: Get up around 9am, commute to work. Come home around 8pm, have dinner, spend some time with my wife and around 11/12pm, I’m in my home office. That goes well into the small hours, around 5am. I do that for a week or two, then rest a few days.

That’s a lot of coffee! Where do you get your inspiration to keep that fire going?

The thing that keeps me going, even through the long hours or burnout, is that I’ve always wanted to work on this. I’ve worked hard to get to where I am, and it still feels like a hobby.

Nowadays, inspiration usually comes from photo books, art installations or architecture.

Nowadays, inspiration usually comes from photo books, art installations or architecture. Even just new places — those things take me outside my comfort zone and make my brain spark in different ways.

What are your go-to equipment/ software that you find necessary to do your work?

When shooting, I use a Canon C300 and Sony F5, always with Zeiss Cine lenses. I used to do all my camera operating (and still enjoy it), but Marco Fernandes (my camera op on the Semi Permanent titles) taught me that I’m better off directing.

My only other go-to tool is Cadrage, an iPhone app that simulates a director’s viewfinder. It really helps test shots and framing everywhere I go. It’s very addictive for any budding cinematographer.

I really can’t work without Photoshop. I do everything on it. I don’t use 3D at all, and use Photoshop to distort and mash up stuff. I’ve been using it for many many years now.

Do you feel that not using 3D limits your creative abilities? Did you make a conscious decision to separate your process from computer generated imagery?

It started as a consequence of not knowing 3D programs, and it guided my work in a direction of photography and minimalism.

As it happens, that’s actually the work I prefer doing. Ever since then, it has at times set me apart from the rest, which in turn helps me get work I enjoy doing the most.

I’ve used 3D at times, when it makes sense, of course. But it doesn’t feel natural to me, and I’ve always found that working around it has made me find better results.

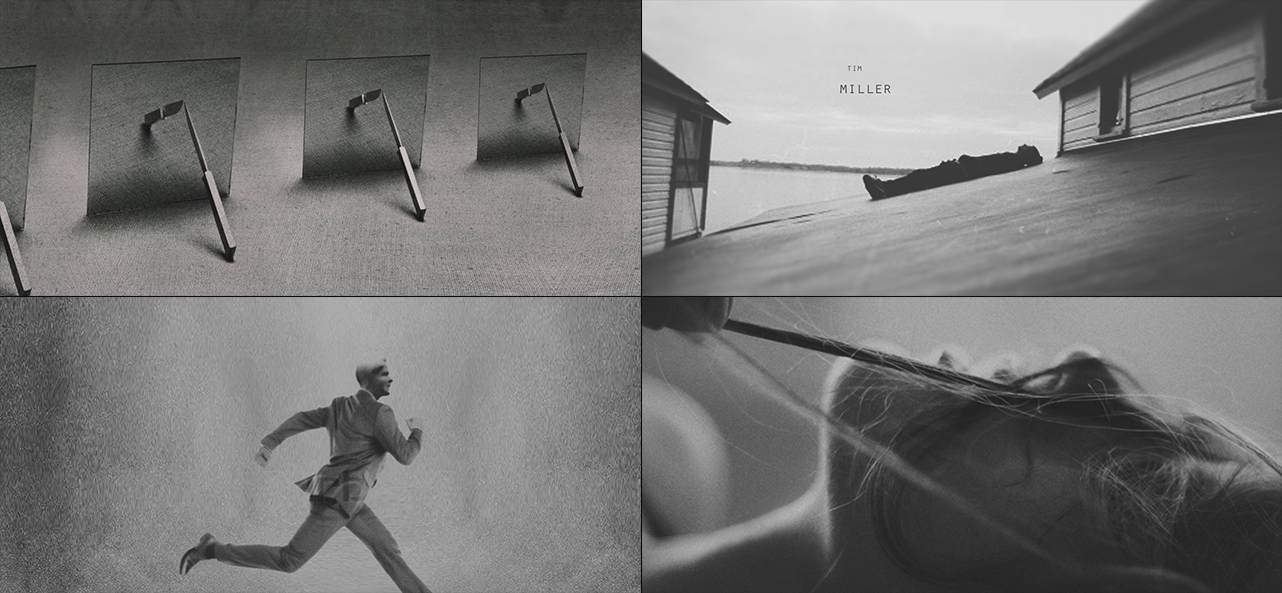

Your title sequence for ‘The Architect’ is cinematic and elegant. Can you explain how that project came about? What does it mean to you?

I wanted to do a title sequence, start to finish, on my own. And I wanted it to be a homage to classic thriller movies, the kind that came out in the 70s. I took 4 months out of my schedule to do it and fixed a deadline to deliver it.

Architecture, film, photography, minimalism — all my influences kicked in and helped shape the concept and direction. I even wrote a small background story for it, something about an architect who’s going insane and wants to take back control of his life, so he builds a model city made of glass and wires and obsesses over it.

I did a ton of research and concept development. I shot everything myself in my office using plexiglass boxes, wires and a lightbox. Exterior shots were captured in and around Lisbon, and some in the Azores islands.

This was the project that got me into working with LA studios and got me really involved with title sequences. Personal projects really do pay off.

There is a lot of play between light, shadow and composition in your work. Can you explain your design philosophy?

I usually try to base everything off of one good image. If the concept behind it is visible and powerful, and it resonates with both the brief and the audience, then you’re golden.

Light and shadow help make something look iconic; same with negative space. It lets the mind fill in the blanks, and that brings the audience in.

What do you enjoy most out of your creative process?

The process itself. I love coming up with ideas and visual sleights of hand. More than worlds, I’m interested in creating moods. Sometimes you can touch somebody in a few seconds or with a single shot. That’s what photographers do with stills and what architects do with light on a wall.

Comparing the earliest work you did at Digital Kitchen to the work you’re doing now, how have you evolved?

I think I’m more mature in my options. I’m not rushing to meet deadlines or proving myself all the time. I want to try new approaches to briefings, I’m more interested in really understanding the projects and make stuff that’s memorable and endures the test of time.

Speaking of creative evolution, do you have any goals that you’ve set for yourself?

I’ve been thinking about setting up a studio here in Lisbon and working exclusively for US clients. Some things are lining up, so we’ll see. For the long run, the ultimate goal is directing my own film.

Are there any designers or studios who’s work hits the spot for you?

I love Alan Williams’ (of Imaginary Forces) “Vinyl” title sequence. That one came out of left field and really hit hard. It’s one of the most raw and powerful titles in recent years, and I know Alan really poured his heart into it. It shows.

For branding, Gretel. They’re the ones to beat right now — the Pentagram of broadcast. Really strong work.

What is the most important trait makes a good designer/ director?

Dedication is key. You have to dedicate yourself to understanding the projects, to come up with fresh ideas and you have to have real dedication to be able to put up with the long hours and stressful days. You have to really want it.

Do you have any hobbies or things you do outside of designing/directing?

I try to spend as much time with family and friends as possible. Other than that, I love traveling to different countries. I sometimes wonder about spending the rest of my days doing miniature models, reading books and just going out taking photos.

You directed this year’s Semi Permanent titles. Was that something you pitched on?

Murray Bell, Semi Permanent’s founder, called me up wondering if i’d like to do the titles for this year. I obviously jumped at it! The previous titles designers had referenced me, so I was very humbled to do it.

What was working with Murray Bell like? Did he give you any brief or did you have carte-blanche on the titles?

Murray gave me a few notes on what Semi Permanent is to him, and where he sees it going. It’s been changing over the years, and it’s evolved into many different aspects — so it’s now more than an event and more of a creative platform.

It has many different layers. That idea of layers and things-within-things kind of gave me the initial idea to talk about what a designer’s life is: seen from inside and outside, everything that connects with it, every cause and consequence.

I showed him a few references and early frames, he liked it, and I was off to build the thing for nearly five months.

What were the specific challenges that you had during the process of creating the open?

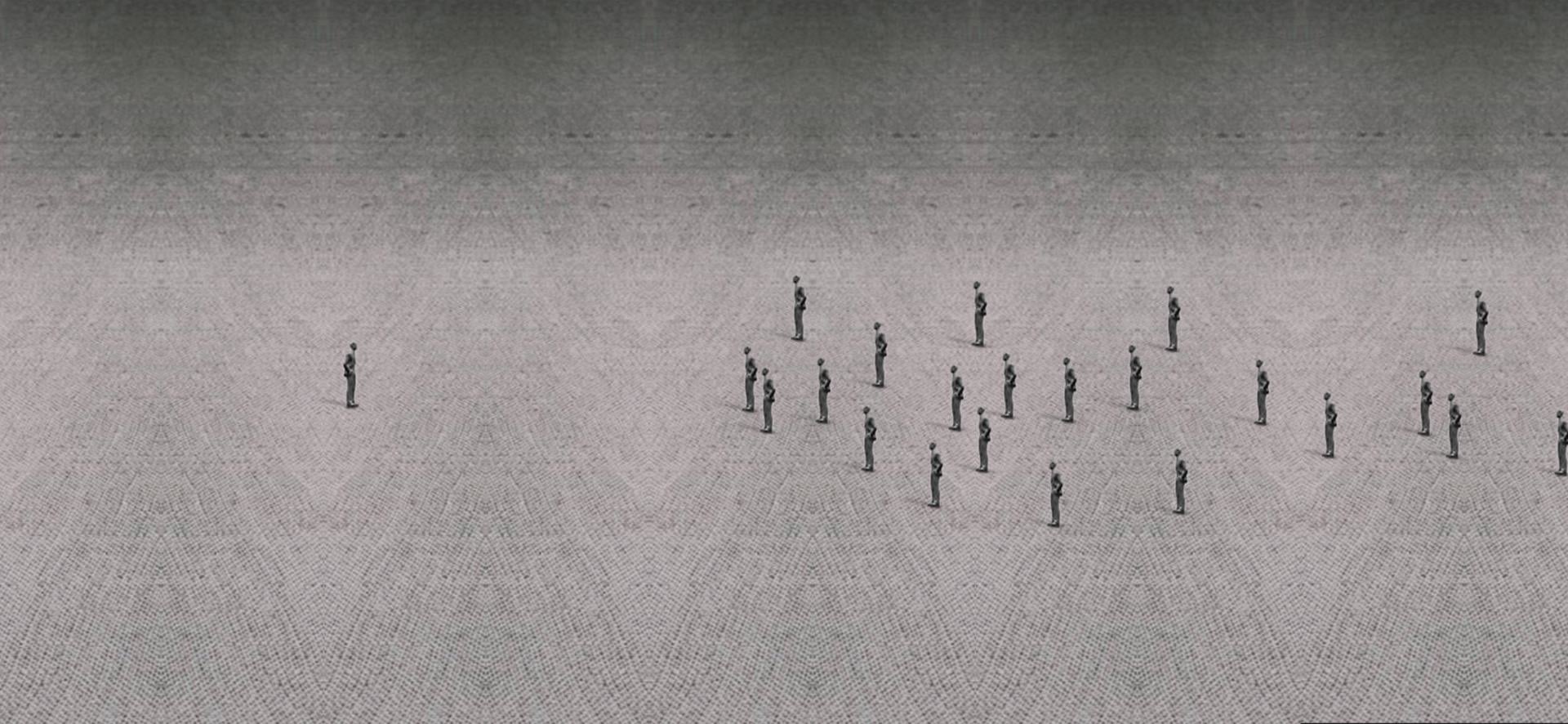

I set out to do something different. I wanted to steer away from the design-oriented titles of before and also to stay away from the 3D abstract stuff that you see so much of.

Concept wise, I approached it as a manifesto for the design community. The story of someone who’s gone through ups and downs, striving to be the best he can be, which is something that resonates with everyone. For me, that meant live action — to really go for the emotional aspect of it. The personal story.

I partnered up with the place I work at, Até ao Fim do Mundo, who helped produce and shoot it.

I also had some invaluable help from Toros Kose in New York, who captured some amazing skyline vistas and interactions with an actor friend of his. He was a great help on everything. Sometimes he served as a sounding board during moments of stress and doubt.

Toros Kose shot some material in NYC

Danny Yount was also kind of my mentor on this one. He kept me focused on what was important.

It was a big shoot: 10+ plus locations, kid actors, lots of setups. I had a sizable crew working with me, and it was my first time with such a big team. It went really well, and everyone was so kind and generous.

Getting Tom Waits voiceover was hard right up to the very end, but we finally got the permission.

Working with so many people internationally, with a sizable cast and locations sounds like an enormous task to direct.

I had a lot of help. Everyone worked pro bono on this, so it felt like a family from the start. We already knew each other, but we had never actually done anything together up to this point.

There were some crucial people, from my DP Ines Rueff to my producer Luis Gonçalves, who kept the whole thing flowing smoothly. I had done some small shoots, mostly for promos and show opens, but nothing like this. So I was learning on the job.

I had a clear vision of what I wanted. The boards and animatic really helped show everyone what we were going for.

Google recently made a short-documentary about you and your efforts into making the Semi Permanent titles. Can you explain what this is and how that came to be?

Early on, Google was very interested in documenting the whole process of doing this title sequence because I was collaborating with people remotely (USA, Australia, Portugal). We used a lot of Google Apps all the time, exchanging files and documents and doing conference calls.

Attention spans are getting shorter but at the same time, there's this growing appetite for good stories.

It turned out to be a great example of group collaboration, all over the world, working on a common goal. They shot all around Sydney, documenting the whole process, and generally just followed me around everywhere. I felt like a Kardashian.

Did Google reach out to you? When and where can we expect to see Google’s documentary?

Google is a sponsor at Semi Permanent, and they saw this as an opportunity to really get involved with the event and the audience in unprecedented ways. Google Apps was really interested in exploring that angle of how we all worked together.

So with all the attention the motion design is getting these days, where do you see the field heading?

Attention spans are getting shorter but at the same time, there’s this growing appetite for good stories. So motion graphics and visual storytelling in general have to transform and adapt. We have to be more efficient at taking advantage of people’s attention.

I think “less is more” here has a real impact: you only have a few seconds, it better be damn good.

Of course, no interview would be complete without asking you for advice. What can designers/ directors do to take their work to that next level of excellence?

It only takes dedication. If you really want it, go for it. But be aware that this means a lot of work.

And don’t be afraid to try. The worst that can happen is that nothing happens.