“So what exactly do you do?”

It’s a question that artists of all kinds recognize well. From fine art to commercial industries, explaining your practice can feel like an uphill battle. Not only does it involve presenting your passion in an understandable package, but it’s common to receive doubt about its validity as a career.

When I am asked to explain my craft as a Concept Artist, I think back to my earliest sources of inspiration: a fascination with storytelling that began at a young age and evolved with me. I found myself insatiably curious about the minds behind my favorite creations. I wanted to push past my perspective as a viewer and understand how each individual piece of the process fits together. Most importantly, I wanted to contribute, aspiring to become one of the many artists behind stories like the ones I connected with.

This goal, in combination with my love for Illustration and writing, led me to Concept Art.

Hayao Miyazaki, Howl’s Moving Castle, 2004.

DEFINING CONCEPT ART

A Concept Artist, in their simplest form, develops ideas for different types of media (most often centered around animation, games, and film). It is the earliest visual representation of a project’s key components, serving as a guide for every following stage of production.

The ability to take ideas and translate them into visual representations is a skill that requires a mind both attuned to visual storytelling and realistic design application. It is the birth of what a final product will become.

Despite this, it is a field that often goes unacknowledged. Those uninvolved with media pipelines tend not to recognize it, executives seek to streamline the process, and secrecy is often required due to company guidelines.

Many artists, young and experienced alike, see it differently. Concept Art should remain a valued practice, as it is the work of these artists that is a key ingredient for a successful project.

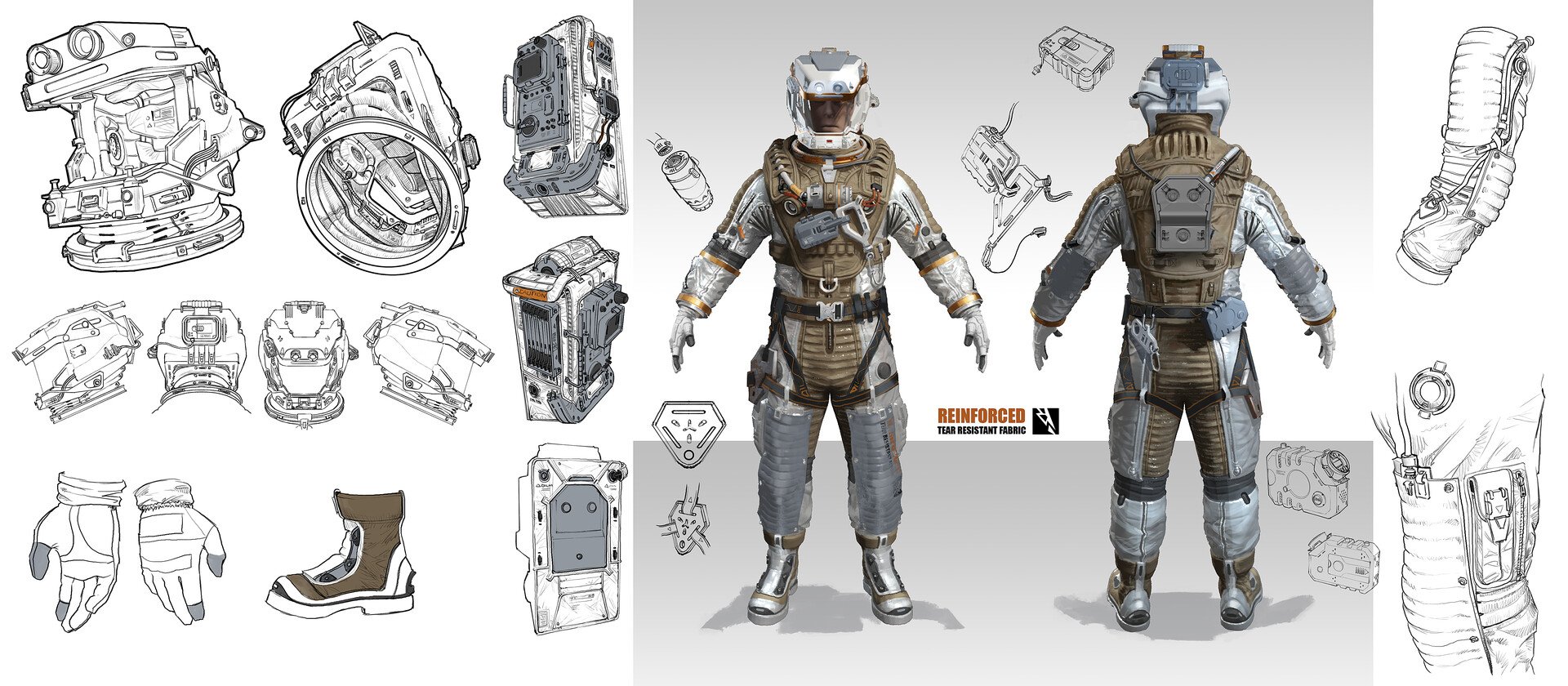

Grant Hiller, Starfield Concept Art, 2025.

HISTORY

Although modern industry standards may make it seem relatively new, Concept Art has been around as long as film, animation, and games have.

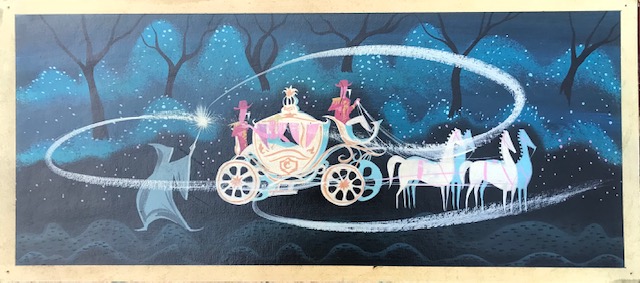

The term “Concept Art” began with Walt Disney Animation Studios in the 1930s, used to describe the early artwork that inspired the worldbuilding and development of media. A notable early example is Mary Blair’s work for Disney. While with the company, she created many paintings that contributed to movies such as Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951), Peter Pan (1953), and more. The striking, vivid look of her work had a direct influence on the style of early Disney classics.

Mary Blair, Cinderella, 1950.

Mary Blair, Alice in Wonderland, 1951.

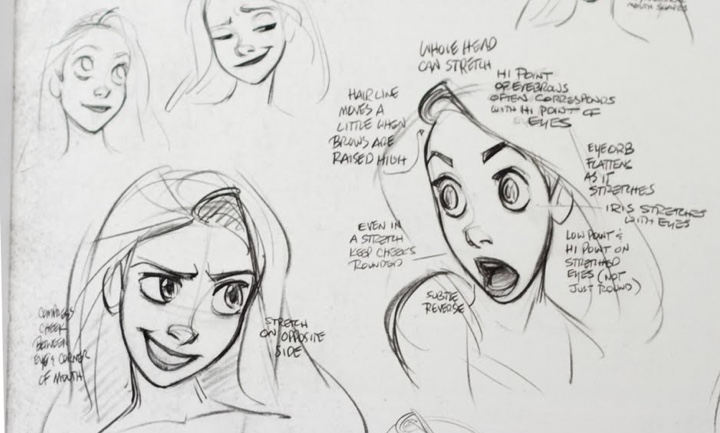

Another iconic Disney artist whose influence on Concept Art can not be understated is Glen Keane. Over the 38 years he spent working for Disney as a Character Animator and Illustrator, he played a pivotal role in shaping the visual language of many films including The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), and Tangled (2010). With each project, he brought a refined and expressive approach to character design, with a focus on gesture, emotion, and strong silhouettes. Endless loose and dynamic sketches were created to perfect Ariel’s tail design or nail Rapunzel’s expression, all working to greatly inform the storytelling integrated into the final animation.

Glen Keane, Ariel Sketch, 1989.

Glen Keane, Rapunzel Expressions, 2010.

Concept Art also has roots in film. Even without the need to design characters or settings for animation, visualizing ideas in the pre-production stage is extremely beneficial for cinema. One of the pioneers in this industry is Ralph McQuarrie, whose paintings brought the world of Star Wars to life. He worked directly with George Lucas to illustrate scenes from the film both for the 1977 movie’s pitch and during its production, designing concepts for both the characters and sets. McQuarrie’s work was a blueprint for the film’s visual identity and his influence continues to inspire Concept Artists who seek to build tangible worlds through their art.

Ralph McQuarrie, Star Wars Concept Painting, 1977. (C) 2016 Lucasfilm Ltd.

Ralph McQuarrie, Painting for Empire Strikes Back, (C) 2016 Lucasfilm Ltd.

The names behind the history of game art are less documented, but their part in its evolution cannot be understated. As games evolved from the pixel art of the 1980s to the realistic graphics of today, countless illustrators were behind the designs created for modelers, worldbuilding, textures, and even box art/promotional materials.

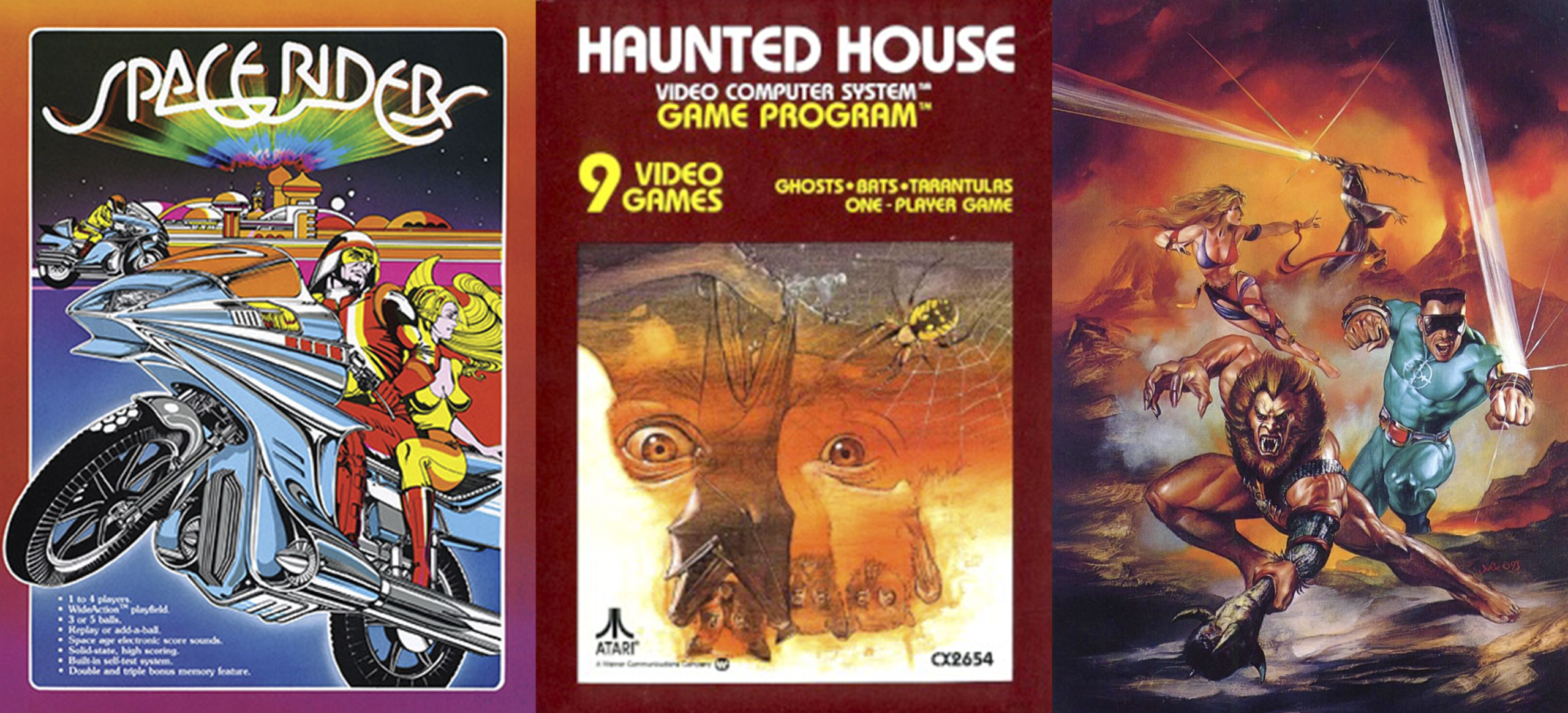

Artists who worked with Atari such as George Opperman, Rick Guidice, and Steve Hendricks created iconic covers while working with very limited graphics, utilizing Concept Art to sell the experience of the game. Of course, this practice wasn’t exclusive to Atari: in the 1990s, artist Julie Bell created vibrant, fantasy style box art that drew attention to the characters and gameplay.

(From Left to Right) Box Art by George Opperman, Steve Hendricks, and Julie Bell.

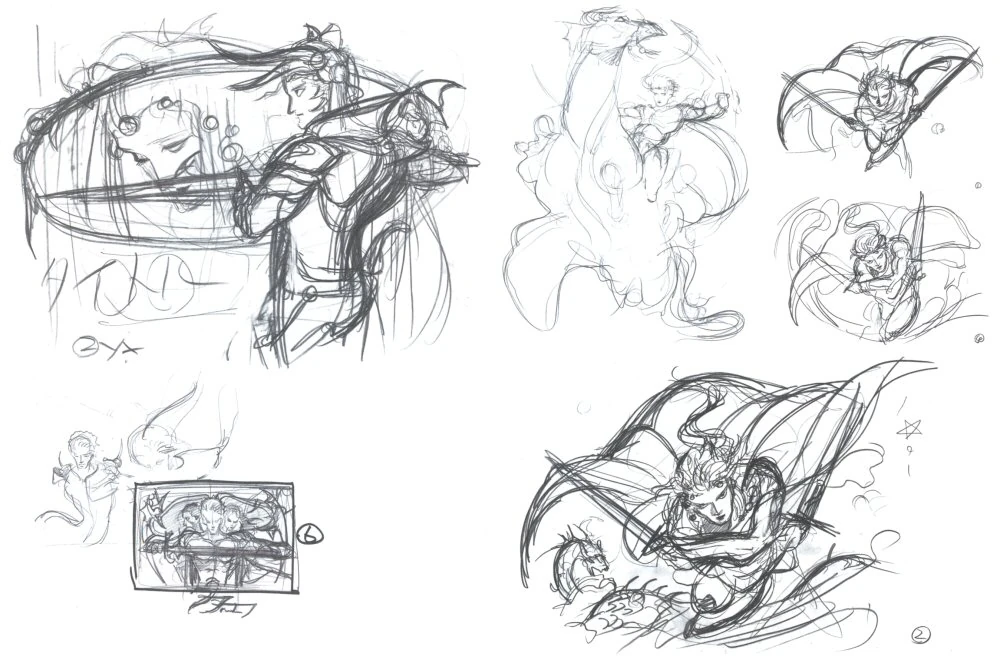

Similar to the video game Concept Art of today, Yoshitaka Amano contributed towards the visual style of the Final Fantasy series, beginning with the first game in 1987. He created Concept Art, Character Design, logos, and promotional art, using graceful figures and dreamlike qualities to capture the overall feeling of the games.

Yoshitaka Amano, Concept Sketches for Final Fantasy, Final Fantasy II, and Final Fantasy III.

Yoshitaka Amano, Promotional Artwork for Final Fantasy V, 1992.

All throughout the evolution of these mediums, there are prime examples of the impact that early illustrations have on final results. Without the unique stylistic contributions of these artists, the final products wouldn’t have the characteristics that resonated with so many people.

As modern programs and practices bring change to the industry, there are countless Concept Artists and Illustrators currently making similar impacts to our predecessors every day.

FEATURED ARTISTS

To illustrate this, I spoke with three artists whose insights shed light on the world of Concept Art and Illustration, from its daily practices, to its challenges, to what their creative practices mean to them.

Eduardo Peña is an Art Director and Production Designer who specializes in creating Concept Art for IP development. His experience includes work in animation, film, and immersive media, as well as his development of original IPs with an emphasis on worldbuilding to explore myths and cultures.

Eduardo Peña, KIZAZI-MOTO / Surf Sangoma, 2023.

Further expanding on Concept Art in the film and video game industries, Léa Pinto is a Visual Development Artist and Background Painter who has collaborated with a variety of clients. Both her client work and personal exercises alike use colorful stylization and plenty of detail to capture grounded subjects.

Léa Pinto, Bob’s Bakery, 2024.

David Palumbo is a freelance illustrator known for dark and atmospheric paintings, who has worked with clients in publishing, comics, novels, and TTRPGS. His perspective as a traditional illustrator in other freelance industries, while different from the featured Concept Artists, adds variety to the discussion of creating illustrations for clients and diverse industry pipelines.

David Palumbo, Binti, 2025.

Together, both these histories and current voices paint the picture for why Concept Art matters, not only as an industry role, but as a foundation in visual storytelling. This article serves as the first entry in a larger series dedicated to exploring the importance of Concept Art through the lived experience of the artists who practice it.

In the pieces to come, the series will dive deeper into the creative process behind Concept Art, the challenges artists face within evolving industries, and where the field may be headed next, all guided by insight from the three featured artists.

Part 2: “Keeping Visual Storytelling Alive: The Importance of the Concept Artist — Part 2”