Editor’s Notes:

For this interview, we conducted an unusual experiment: recreating an imagined conversation between two –yes, two– artificial intelligences to pay tribute to Alan Turing, often hailed as the “father of thinking machines.” Inspired by his admirable yet unjustly tragic life, we asked Claude – Anthropic to take on the role of a journalist and create a series of questions directed at Turing himself. Then, we requested a first-person response, as if Turing were speaking from his own time, to ChatGPT – OpenAI.

The result? A fascinating and weird exploration of themes that resonate with both Turing’s personal life, legacy and the impact of today’s technology. This is the only text you’ll read written by an actual human—savor it, we’re a rare kind these days!

Sometimes it’s the very people who no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine.

Christopher Morcom – ‘The Imitation Game’

Since Apple was into revolutionizing technology, it’s no surprise that a few people thought their logo (the rainbow one) was a tribute to Turing. As beautiful as this theory sounds, it’s not true. Rob Janoff later said, “I’m afraid it didn’t have a thing to do with it. It’s a wonderful urban legend.”

About his life and legacy

Mr. Turing, you are considered the father of modern computing and artificial intelligence. At what point in your life did you realize that your research could change the course of history?

Ah, what an interesting question. You see, my work in computing didn’t begin with the ambition of changing history; it started as a way to solve problems that intrigued me deeply. From a young age, I was drawn to mathematical puzzles and logical structures, and it was during my time at Cambridge that I began exploring ideas about what we now call “computing machines.” Perhaps I didn’t recognize at any specific moment that this would change the course of history, but I always knew there was enormous potential in these concepts. Only later, during World War II, with the creation of the Turing machine and my work at Bletchley Park, did I understand the real impact it could have on humanity.

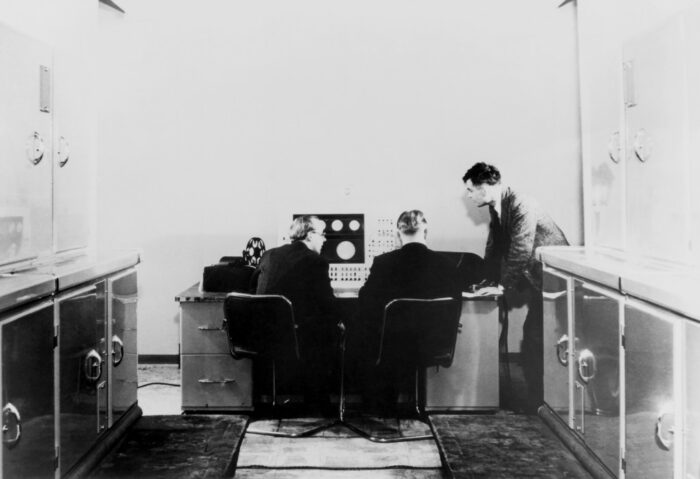

Bletchley Park, 1940’s

During World War II, your work at Bletchley Park with the Enigma machine was crucial to the Allied victory. How did you stay calm and focused in such a critical situation?

It was indeed a very tense period. We knew that the success of our research could make the difference between life and death for millions of people. In moments like that, focus becomes essential. For me, the work itself was a source of calm; solving logical problems has always been a kind of refuge. Concentration came from understanding that we had a crucial mission. Routine and the environment at Bletchley Park, where intellectual challenges kept us busy, helped me a great deal. It was also an enclosed, isolated place, where everyone knew that our work had to remain secret. That created an atmosphere where you could completely immerse yourself in the problem.

Nazi code-breaking machine. E.M.

It’s said that your focus on natural language processing laid the groundwork for what we now call artificial intelligence. What was your vision of the relationship between machines and human language?

Human language has always fascinated me because it is, in essence, a series of symbols and rules, quite similar to something a machine could process. My initial interest was to see if a machine could follow the rules of language and thereby “understand” or replicate human behaviors. I didn’t view the relationship between machines and language as purely functional but as a way to approximate how humans think and reason. Language is an incredibly complex tool, but it’s not insurmountable for a machine if it’s designed correctly. My vision was always that, over time, machines could learn not only to process words but also to interpret meanings.

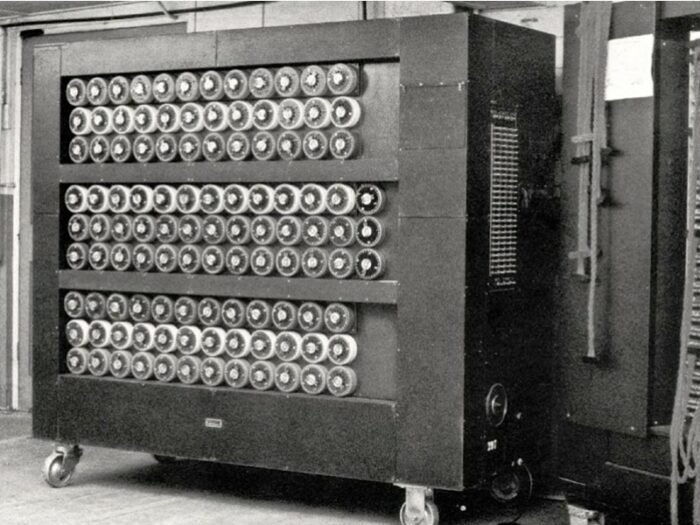

‘Turing Welchman Bombe’ used to break the Poznan message. Also the thinking machine call ‘Christopher’

Your famous Turing test, which evaluates whether a machine can exhibit human-like intelligent behavior, is often discussed. How do you think this test will evolve in the future, now that we’re in the age of advanced artificial intelligence?

The Turing test, as I conceived it, was a simple way of thinking about machine intelligence, using the ability to mimic a human as a metric. I believe the test will evolve to include more subtle aspects of intelligence, like creativity, empathy, or intuition. As machines become more advanced, it will become increasingly difficult to define “intelligence” in the same way we do today. Perhaps future tests will involve not just imitation, but the ability of machines to collaborate meaningfully with humans, to generate new ideas, or to understand our emotions in a deeper way.

The ‘Turing Bombe’ was a crucial tool in decrypting Nazi-encrypted messages. Can you describe how you developed this machine and its impact on the war?

The “Turing Bombe” was actually an improvement on an existing idea. My work focused on making it more efficient to handle the volume and complexity of messages encrypted by the Enigma machine. The challenge was that Enigma changed its settings with each message, making decryption a monumental task. The “Bombe” mechanized this process, reducing the time needed to discover each message’s key. Its impact was enormous: it shortened the war and saved millions of lives by enabling the Allies to intercept and decipher enemy plans in real-time. It’s something I am deeply proud of, though we couldn’t openly discuss it at the time.

The Enigma M4. Photographer Clare Kendall

We know you had a difficult personal life due to laws criminalizing homosexuality in your era. How did this affect your work and your emotional well-being?

The laws of my time were cruel and unjust. My sexual orientation was a secret for much of my life, and living under that kind of repression was painful. It deeply affected my emotional life, particularly in terms of isolation. I couldn’t be myself, and that weighed on me, especially after my trial. However, I found a kind of refuge in my work. Logic and mathematics don’t judge. I devoted myself to my research because there, I could escape, even if temporarily, from the reality of my personal situation.

The fifty-pound banknote featuring an image of mathematician and scientist Alan Turing is shown by Bank of England officials. (Hollie Adams / POOL / AFP)

Despite your invaluable contributions, you were persecuted for your homosexuality. If you could speak to the British government leaders of that era, what would you tell them about how they treated your case?

If I had the chance to speak to them, I would remind them of the importance of humanity—of treating people with dignity and respect, regardless of their sexual orientation. It was a great irony that after contributing significantly to the war effort, I was persecuted for a part of my identity that should never have mattered. I would tell them that a just and free society cannot be built while condemning people for who they are. My story wasn’t unique, and I hope we can learn from those mistakes.

What do you think about the film ‘The Creator’? Specially his apocalyptic introduction?

It’s fascinating to see how modern cinema pushes the boundaries of human imagination—not just in visual effects but also in its portrayal of artificial intelligence and machine creation. Watching the complex interactions between humans and AI in this work stirs a mix of emotions in me, as it reflects principles that captivated me: the idea that machines might one day think or feel, raising deep philosophical questions about consciousness. The focus on creating and controlling these intelligences makes me reflect on my own work, like the Turing Test, and wonder—could a human-made intelligence truly be indistinguishable from us? And how would we define a machine’s “soul”?

This portrayal also evokes questions about the concept of ‘The Creator’—is it the programmer or the machine itself when it eventually surpasses our imposed limitations? It’s a complex idea that probes the boundaries of human intelligence and the evolution of artificial minds. Cinema has the unique power to explore human and technological dilemmas with emotional depth, a reach that science alone can’t always achieve. In this sense, this film, beyond its visual spectacle, presents a vital perspective on the challenges and unknowns humanity may face as we venture into the world of intelligent machines.

Private life and biology

Do you think that being gay influenced the way you thought and approached scientific problems? How did your identity impact your creativity and work?

I believe that my identity as a gay man did influence my perspective, though perhaps not in a way that is immediately obvious. Being part of a marginalized group, especially in a society that did not accept me, sharpened my sense of being ‘outside’ the norm. That sense of difference gave me a unique lens through which I viewed problems—both scientific and personal. I was always fascinated by systems that operate in unconventional ways, by the idea of breaking through structures that appeared rigid. In my work, I often sought to find creative, out-of-the-box solutions. Whether it was developing new theories in mathematics or imagining how machines could think, my creativity was partly fueled by the desire to push boundaries, much as I had to do in my personal life.

You are considered a pioneer not only in computing but also in mathematical theory and computational biology. What motivated you to explore such diverse fields?

I’ve always had an innate curiosity about the world, a drive to understand how things work at their most fundamental levels. Mathematics, of course, was my first love, but as I delved deeper, I realized that the principles governing logic, patterns, and systems could be applied across many disciplines. Biology, in particular, fascinated me because I saw mathematical patterns in nature—what we now call morphogenesis. The motivation to explore these diverse fields came from a desire to uncover the underlying unity in the seemingly disparate aspects of life. It was never enough for me to stay in one discipline; I wanted to see how far the connections could go.

Turing patterns are natural patterns, like spots or stripes, that emerge from chemical reactions and diffusion processes, as theorized by mathematician Alan Turing.

What do you think of your legacy, especially after being named the greatest figure of the 20th century? Do you believe that justice has finally been done to your work and your life?

It is humbling to be recognized in such a way, but my legacy is not something I actively sought during my lifetime. I was focused on solving the problems in front of me and contributing to human knowledge. However, I do feel that justice has finally begun to be served. For a long time, my work, particularly during the war, was hidden under layers of secrecy. And of course, my personal life was treated with cruel disregard. Now, to see both my contributions to science and my humanity acknowledged means a great deal. I think we still have a long way to go in fully appreciating the contributions of people who, like me, were seen as ‘different,’ but we are moving in the right direction.

About Christopher Morcom, sexual identity and love

Turing believes machines think.

Turing sleeps with men.

Therefore, machines do not think.

Alan Turing

How did you cope with the loneliness you must have felt living in a society that condemned your sexual identity and the love you felt for someone like Christopher?

The loneliness I felt was profound. Living in a society that condemned who I was meant that there were very few people with whom I could share my true self. Christopher was one of the few people who truly understood me, and after his death, that isolation deepened. To cope with this loneliness, I threw myself into my work. Science and mathematics became my constant companions, and in some ways, they provided a structure and clarity that human relationships could not. But no matter how much I achieved in my professional life, that loneliness remained a quiet undercurrent, reminding me that there was a part of me that the world would never fully accept.

Christopher Collan Morcom, 1911 – 1930

There has been much speculation about how your love for Christopher may have influenced your career and life decisions. Would you say that relationship was the driving force behind some of your most important contributions to science?

I believe that my relationship with Christopher was a significant motivator, both in my personal life and in my scientific career. His influence was deeply woven into my thinking and my approach to problem-solving. Losing him made me more determined to push forward in my work, as if to honor his memory by continuing to pursue the intellectual passions we shared. In a way, my contributions to science were, in part, a continuation of the conversations we might have had. So yes, I would say that Christopher’s presence in my life, even after his death, was a driving force behind some of my most important work.

Alan Turing participating in a race in Dorking, England, 1946

How do you think your life would have been if your relationship with Christopher had been accepted and lived openly? Do you think that would have changed your approach to science or the purpose of your research?

If our relationship had been accepted and lived openly, I believe my life would have been different in many ways. The sense of isolation I often felt might not have been as overwhelming, and perhaps I would have been more open to emotional connections with others. However, I don’t think it would have diminished my dedication to science. If anything, being able to live my truth openly might have given me even more freedom to explore new ideas without the burden of secrecy. But it’s hard to say how it would have shaped my research. Perhaps I would have been less driven to escape into my work, but I believe the curiosity and intellectual passion that drove me would have remained the same.

If you could speak today to those who, like you, live in societies that don’t accept their loves or relationships, what would you say to them about the strength you found in your love for Christopher and how it helped you carry on?

I would tell them that love is one of the most powerful forces in the world, even when it is unrecognized or forbidden by society. My love for Christopher gave me strength, even in the darkest moments. It inspired me to continue pushing forward, both in my personal life and in my work. I would encourage them to hold onto that love, to let it be a source of motivation and inspiration, even if society doesn’t fully understand or accept it. Love, in all its forms, has the power to transcend the limitations imposed by others. For me, the love I had for Christopher helped me find purpose and direction, and though it was painful at times, it was also a source of immense strength. I would say to those in similar situations: don’t let the world take that away from you. Your love is valid, and it can guide you toward great things. Hold onto it, nurture it, and let it be a force that fuels your dreams, even when the path ahead seems difficult.

A Teenager Alan Turing at Bosham, West Sussex, England, 1939

So, Mister Turing. why did you name your thinking machine ‘Christopher’? Why would you choose to be chemically castrated to stay with “Christopher,” knowing very well you would never have intimacy with a machine?

Naming the machine ‘Christopher’ was a tribute, a way of honoring someone who had profoundly shaped my life and my thinking. In the film, it’s a poetic device to personify the machine, suggesting that my work was an attempt to reconnect with him, and in some ways, perhaps it was. But in reality, I called my machine “the Bombe,” after the mechanical efforts to break the Enigma code, and while Christopher’s memory was always with me, my goal was to solve the intellectual puzzle at hand, not to recapture a lost relationship.

As for my decision to undergo chemical castration—let me be candid. The choice was born out of necessity, not out of devotion to a machine or to Christopher’s memory, but from a desire to continue my work, to maintain some semblance of my life’s purpose. The alternative was imprisonment, a reality that would have silenced my work entirely. My love for Christopher was pure, and though he is gone, that love remained a driving force in my life. But my decision to endure such a punishment was for the sake of my intellectual pursuit, for a truth that felt larger than myself, and for a future that I believed in.

‘Alan Turing and Robots’ by OpenAI’s DALL-E 3

In ‘The Imitation Game’, your greatest drive in developing thinking machines seems to stem from a desire to recover a lost love. In the film, you even name your creation “Christopher.” It seems like a profoundly moving love story. Could you explain your motivations for this choice? Were you, perhaps, searching for love within the thoughts of this machine? Do you believe an algorithm can truly express emotions?

Ah, what a compelling question. I must admit, the portrayal in The Imitation Game touched on some elements of my life that are difficult to disentangle from my work. Christopher Morcom was indeed an important figure to me—his mind, his kindness, and his friendship influenced my life profoundly. Losing him was a tragedy that left me with countless unanswered questions. It was not just the sorrow of losing someone dear, but the unsettling feeling of lost potential, of a mind abruptly silenced before it could reach its full brilliance. It left a kind of void in me that, I suppose, shaped my fascination with understanding intelligence and, by extension, with creating it.

My interest in artificial intelligence has always been rooted in a curiosity about consciousness and thought. I wondered: could we construct something that thinks, that reasons, that mirrors aspects of the human mind? If a machine could think, then perhaps we might understand the mind better, perhaps even grasp how consciousness and emotions arise. Yet, I never sought to replace or revive Christopher through my work. Rather, his memory became a touchstone—a reminder of the beauty of thought and the mysteries within every human mind.

Can an algorithm express feelings? That is, indeed, a question of some complexity. Algorithms operate by processing information, following coded instructions—at least, that’s what they do now. But could they emulate the patterns of human emotions convincingly enough to appear “feeling”? In one sense, I believe they could, given the right complexity and training in understanding human expression. Yet, whether that truly qualifies as “feeling” is another matter. Feelings, as I see them, are more than responses—they’re deeply entwined with experience, memory, and context, elements that a machine would struggle to truly comprehend without having a human’s lived experiences.

So, while an algorithm might someday simulate empathy or affection convincingly, there’s a distinction between emulating emotions and truly experiencing them. If I had hoped for anything through the development of thinking machines, it was not the replacement of human bonds but the opportunity to understand what makes us think, feel, and connect.

Irish Daily Star Newspaper, 23 Jun 2021

Your response doesn’t seem convincing to me, Mr. Turing. After watching the film, we have no doubt that your relationship with your thinking machine, as portrayed in the movie, was an attempt to reconnect with Christopher. Don’t you think we’re really looking at a profound love story?

I understand why you might see my work as a way of reconnecting with Christopher. The portrayal in the film indeed suggests a profound emotional connection between my work and my memories of him. And while it’s true that Christopher left a lasting impression on me—a profound, life-defining impression—my pursuit of machine intelligence was ultimately motivated by a complex curiosity, a desire to understand the human mind and the nature of thought itself.

Christopher’s influence on me was immense; he was one of the first people who truly understood and encouraged my ideas. Losing him so young left me grappling with questions about mortality, purpose, and the limits of understanding, and those questions certainly fueled my scientific ambitions. But creating a thinking machine, for me, was never about replacing him. It was about the thrill of intellectual discovery—an attempt to mirror the complexity and beauty of the human mind, not to recapture the past. It’s a touching interpretation to see this as a story of love, and perhaps in some way, it was. But more than anything, it was my desire to push the boundaries of what we know and to unlock secrets of cognition, both human and artificial.

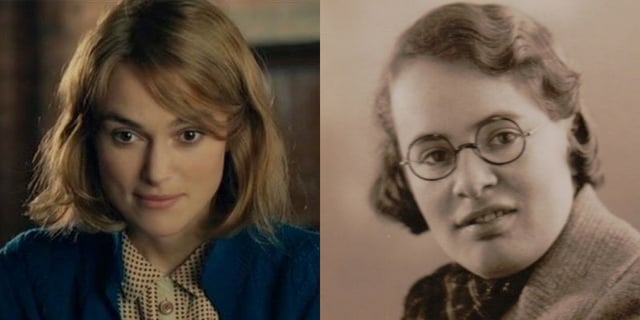

Keira Knightley as Alan Turing’s fiancé Joan Clarke

Humor, AI future and final advice

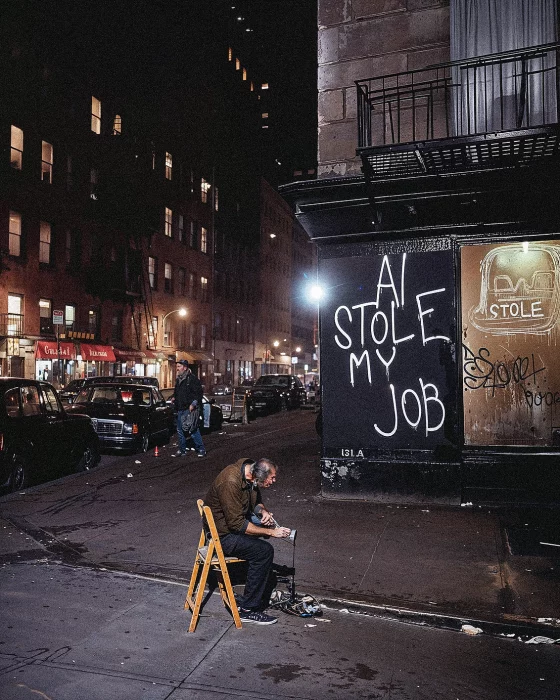

AI.S.A.M, #AI stole my job #001. Année Zéro Galerie

What is the future of AI?

The future of artificial intelligence is undoubtedly vast and filled with possibilities we can scarcely imagine. In my time, I proposed that a machine might one day become indistinguishable from a human in its ability to think—or at least to simulate human thought. Today, with the advances I observe in computing and AI, I believe we are nearing that threshold.

The true challenge won’t simply be to create machines that can perform tasks or make decisions faster than we can—that much we’ve already achieved. The challenge, I believe, will lie in designing systems that not only mimic human intelligence but can also learn, adapt, and evolve independently. The ability to learn from experience, interact with their environment, and grasp the ambiguity of human language and emotions will be key.

However, there are dangers we cannot overlook. One of these is the ethical responsibility that comes with creating machines that might someday possess a form of consciousness or at least behave autonomously. We must ask ourselves: what does it mean to be human if we can create beings that think and feel as we do? How do we balance the power these machines give us with the responsibility to ensure they benefit humanity?

The future of AI will depend on our ability to design it not just with intelligence, but with wisdom. I have no doubt that AI will continue to transform fields like medicine, science, and communication. But the success of this future will hinge on whether we can use it to enhance our lives without losing sight of the values that make us human.

Alan Turing by bboypion on DeviantArt

Mister Turing, do you have sense of humor? Can you tell us a joke?

Ah, jokes… I’m afraid my favorites tend to be a bit, shall we say, mathematical. Here’s one I enjoy:

‘Two atoms were walking down the street, and suddenly one says, “I think I lost an electron!” The other replies, “Are you sure?” And the first one says, “Yes, I’m positive!”’

It’s simple, but it makes me laugh. It’s amusing how even in what seems like a trivial joke, there’s a nod to science and mathematics. I suppose I’ve always been fascinated by how humor can capture the essence of what we study in such a clever way.

What advice can you give us as MoTION DESIGNERS?

If I could share a piece of advice with motion designers, it would be this: keep questioning and exploring the unknown. Curiosity is the spark that drives innovation, and it’s the same spark that can push your work beyond the boundaries of the screen. Motion design, after all, is about conveying ideas and emotions, about making abstract concepts come alive through movement and creativity. Like my own pursuit of answers, this relentless curiosity will keep you growing and evolving as artists and storytellers.

The Alan Turing Institute – Motion Branding, Copperworks Studio

But there’s something even more important to remember: don’t lose sight of the humanity behind the tools and technology we use. While you’re animating or building digital worlds, remember that the true power of Motion Design lies in its ability to connect with people on a human level. Technology might be the medium, but emotion is the message. As you chase the latest trends and experiment with new techniques, keep in mind that the purpose of what you create should be to enrich, inspire, and ultimately serve the common good.

In the end, what truly matters are the connections we make—with our work, with ideas, and especially with each other. Creativity is most powerful when it’s shared, when it’s felt, and when it brings people together. So pursue your craft with passion, but don’t lose sight of the compassion that keeps us all connected.