I remember a long time ago, back in the days of Tween, before Motionographer, I posted a character-driven CG spot by Psyop and off-handedly remarked that it was impeccably designed.

A few hours later, a comment popped up from an anonymous reader. (It’s always the anonymous readers.)

“Design? What design!? This is animation.”

I grumbled to myself and probably wrote a passive aggressive response. I don’t remember. Later, though, I realized there was a lesson to be learned here. While I believed that design — that is, crafting images that solve problems and guide excellence before production even begins — was foundational to successful work, not everyone did.

From both a business and a creative perspective, design — in the form of style frames, concept art, character design and design boards — is what makes or breaks work. It’s the difference between consistently awesome output and sporadically decent results. In short, it’s the difference between winning and losing.

So when SCAD professor Austin Shaw approached me to write the forward for his recently released book, “Design for Motion: Motion Design Techniques and Fundamentals,” I leaped at the chance.

As our interview below shows, Austin’s professional experience and commitment to the craft of design — in all its forms — primed him to write an practical, authoritative book on the way that design and motion work together. Read on!

Interview with Professor Austin Shaw

What exactly is this book about?

This book looks at the last few decades of motion design through the eyes of the designer. I wanted Design for Motion to examine the relationship between image-making and storytelling, providing a framework for students or creative professionals looking to transition into the motion design industry.

Design for Motion defines key terms such as style frames and design boards, explaining how they are used professionally to pitch projects, guide productions, and manage client expectations.

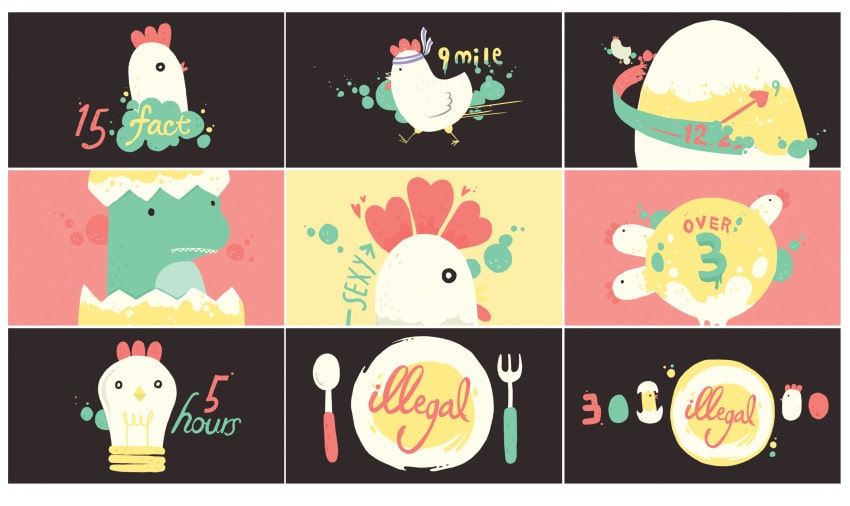

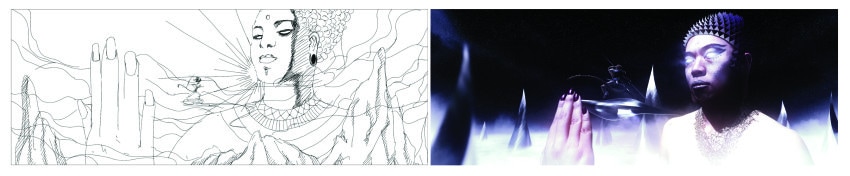

Illustrative design board by Yeojin Shin

More importantly, the book provides practical lessons for learning how to create style frames and design boards. Design for Motion covers concept development, image-making principles, storytelling, basic cinematic principles, compositing for design, and integrating 3D software.

There are also a series of assignments/creative briefs that cover a range of design styles used in motion design, such as type-driven design, tactile design, info-graphic design, illustrative design, and character-driven design.

Tactile design by Gautam Dutta

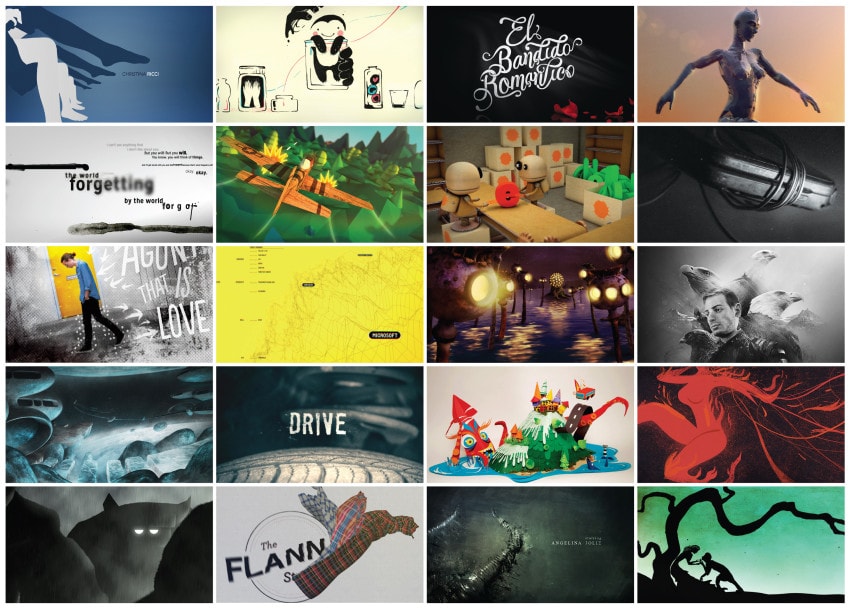

Additionally, I reached out to a number of industry leaders to share their experiences and showcase their work in relation to design for motion. Personal interviews can be found throughout the book in sections called Professional Perspectives. I felt it was important to include insights from top designers, in their own words.

Examples from contributing professionals in the order of appearance in the Design for Motion textbook. Erin Sarofsky, Lauren Hartstone, Carlo Vega, Karin Fong, Lindsay Daniels, Patrick Clair, Alan Williams, Kylie Matulick, Danny Yount, Robert Rugan, Chace Hartman, Will Hyde, Greg Herman, Beat Baudenbacher, Lucas Zanotto, Bran Dougherty-Johnson, Daniel Oeffinger, Bradley G Munkowitz (GMUNK), Matt Smithson, Gentleman Scholar

There are also examples of student work from my Design for Motion courses, to illustrate the principles outlined in the book. As an educational text, my goal is for the book to build a bridge between students and professionals.

Examples of student work included in the Design for Motion textbook. Preston Gibson, Yeojin Shin, Chris Finn, Kalin Fields, Rainy Fu Huifen, Keilang Shan, Nick Lyons, Peter Clark, Joe Ball, Daniel Chang, Vanessa Brown, Sekani Solomon, Peter Clark, Patrick Pohl, Jackie Khanh Doan, John Hughes, Graham Reid, Chris Finn, Ana Cristina Losada, Jackie Khanh Doan

What is the book not about?

This book is not a how-to software book. Industry standard tools and software are certainly mentioned, but I focused on identifying the underlying art & design principles of design for motion.

I would like to think this book is not haughty or condescending. I wanted this book to be approachable, so I chose to write the text using the same voice in which I teach.

Why did you feel the need to write it?

There are not many books out there covering design for motion. Of course, there is a rich tradition of textbooks covering traditional image-making like graphic design and illustration as well as visual storytelling through cinema and animation.

We also have excellent books on motion graphics, but they focus primarily on how to create motion. I felt a need to explore and define the connection between design and motion.

This book emerged out of a desire to teach a course that focused on creating style frames & design boards. That has been part of my professional experience as a designer & illustrator for motion projects.

Style frames for Equator HD network identities by Austin Shaw. Created for Loyalkaspar

I wanted to bring lessons from the industry into the classroom. I had worked as a full-time commercial artist from 2000-2010 before transitioning into a full-time educator. Teaching gave me an opportunity to take a breath and reflect on the previous decade.

What I discovered was that I had put a lot of stress and pressure on myself as a designer – to win pitches, to please clients, and to be awesome ☺.

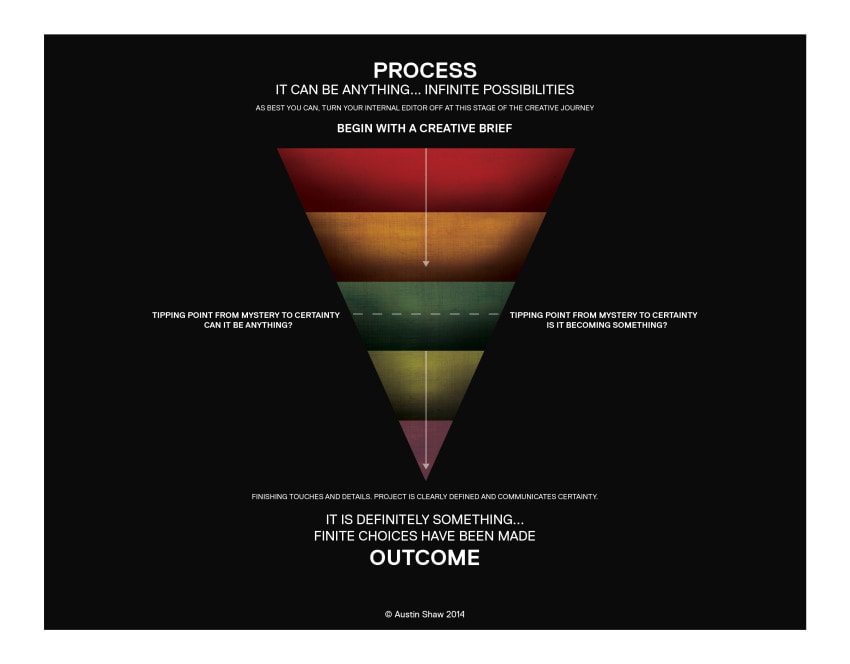

These are all important outcomes, but I had lost some of the joy, passion, and curiosity needed for creativity. I developed an information graphic to illustrate a theory I came up with called the Process-to-Outcome Spectrum. I began teaching students how to use this tool to create the best outcomes while still enjoying the process.

One of the essential lessons I learned in becoming a strong designer was to make a lot of design boards. I believe that grit and dedication are pivotal ingredients for success; however, I noticed that students who lacked foundations in areas like concept development, design compositing, and cinematic visual storytelling were struggling.

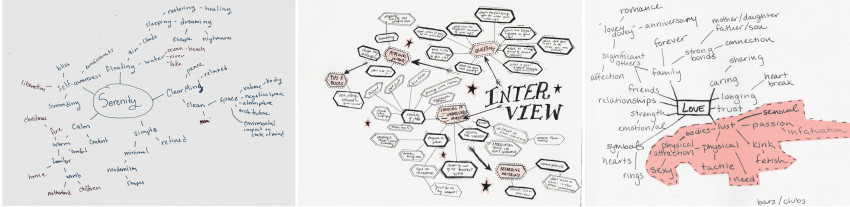

Mind maps by Taylor English, Sarah Beth Hulver, and Lauren Peterson

I realized I was taking for granted all the various skills and techniques that I developed over many years in the work place. Through field-testing in the classroom, I refined and sequenced specific exercises to help develop a comprehensive curriculum to build a foundation in design for motion.

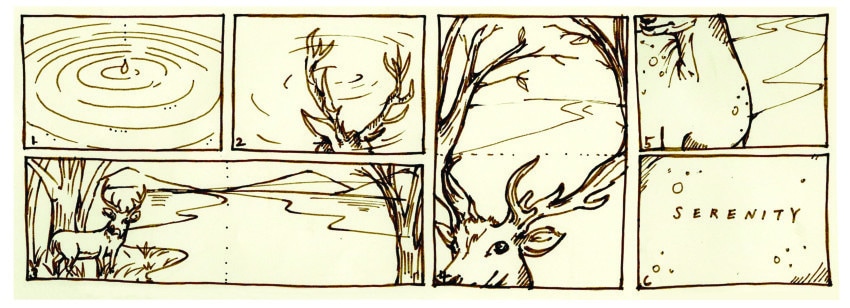

Thumbnail sketch & style frame by Daniel Chang

Hand-drawn storyboard by Hyemin Hailey Lee

How did you professional experience prepare you to write this book?

I have worked as a designer, illustrator, animator, art director, & creative director for studios such as Curious Pictures, Loyalkaspar, Perception, Brand New School, Digital Kitchen, Superfad, and Sarofsky. I have also worked directly with clients like VH1, Nat Geo Channel, and Ralph Lauren.

But I found my way into the motion design industry by chance, rather than by design.

I studied Studio Art at NYU in my undergrad, with a focus on figure drawing & printmaking. I went to graduate school at Pratt Institute to study Art Education, imagining myself as a painter & high school art teacher.

At an academic advisor’s suggestion, I enrolled in a basic design class. A whole new world of possibility opened up, beyond being just a painter or an art teacher. However, I was torn as I really enjoyed teaching. I made a decision to change my major to communication design, with the option to teach in the future, which ultimately became my path.

My training in both fine art and communication design prepared me to be a lead designer on projects early in my career. I began winning pitches while I was still an intern, which allowed me to work closely with creative directors and get a hands-on view of design-driven production.

I quickly learned that if I could animate as well as design, I could stay busy and be regularly booked as a freelancer. So I became a designimator!

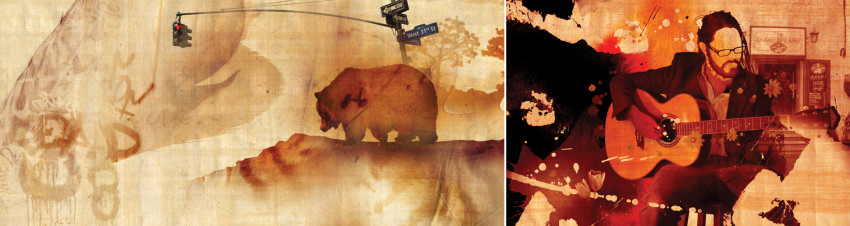

Photo Illustrations by Austin Shaw

I spent many years permalancing at different creative studios in New York City, allowing me to learn from a wide variety of talented individuals. I worked alongside and pitched against talented designers and art directors. I also learned from producers, editors, and live-action directors.

These experiences taught me how the motion design industry works, how to design quickly, how to interact with clients, interpret creative briefs, and observe different types of studio structures.

Why did you leave industry for academia?

Although I found success working as a full-time commercial artist in the motion design industry, I felt like something was missing. I always knew I wanted to teach.

I was given the opportunity to teach as an adjunct instructor at the School of Visual Arts in NYC, and I did that for a few years. Teaching at SVA ultimately opened doors for me to become a full-time Professor at the Savannah College of Art and Design. I am now in my 6th year teaching at SCAD.

Teaching full-time in the Motion Media Design department at SCAD has been an invaluable experience in terms of preparing me to write this book. I am a part of a collaborative community of both faculty and students. My colleagues excel in their craft, and we have an open exchange of ideas.

Information graphic design board by Sekani Solomon

The students are awesome – extremely talented, and willing to put in the work to grow. My time in the classroom, combined with my industry experience, has given me a wealth of both theoretical and practical knowledge to draw upon.

Was there a specific aspect of writing this book that was especially challenging.

There were definitely moments were I felt overwhelmed by the immensity of the project. I also had to face my own fears and insecurities, as each creative person must, and ultimately put my work out into the world.

What helped me was using the same principles & techniques outlined in the Design for Motion textbook. I worked broad, and gradually refined my ideas into tangible sections.

I did a lot of free writing, word lists, and mind mapping to help me form my chapter outlines. I was also blessed to have the help of my wife as my creative editor. She was a huge help with grammar and making sure I was not being overly redundant with both my word choices and ideas.

Where do you see the future of Motion Design heading?

In considering the future of Motion Design, it is important to reflect upon the tradition on which we are building.

I see the industry studio model as a continuation of the classical atelier or workshop from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. A Motion Design production team mirrors the classical model of a principal master, assistants, and apprentices. Now, we have creative directors, producers, art directors, designers, animators, and interns.

I have embraced the term design-driven production to describe the present studio model for Motion Design. I believe it encapsulates the dynamic process and fusion between the individual artist/designer and the collaborative aspects of production.

I believe Motion Design attracts creative professionals who enjoy working fluidly between design & production. These individuals possess the ability to work both on their own and on a team, a transitional skill that is required in our discipline.

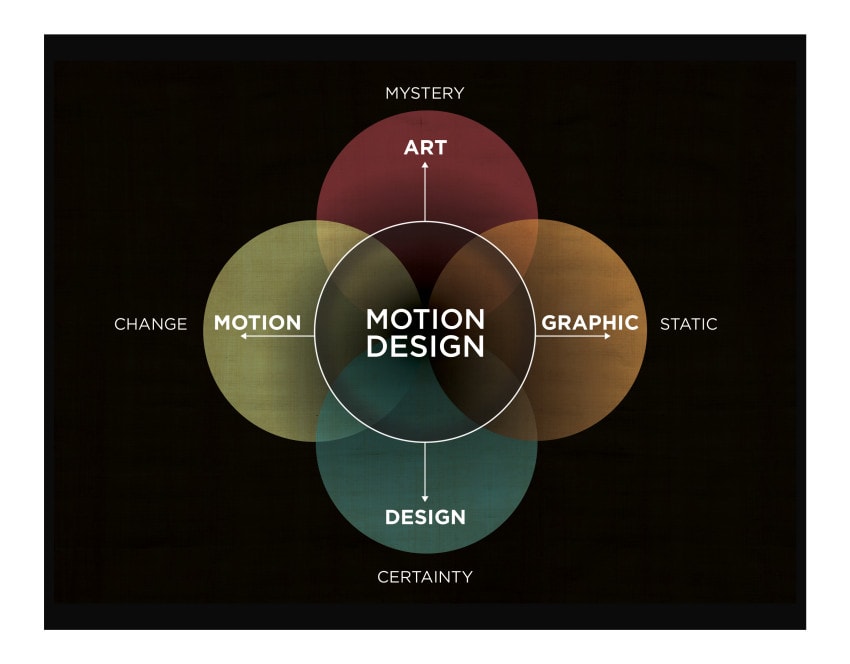

Motion Design is an extremely eclectic discipline – a combination of both motion and graphic media, as well as art & design.

I see the future of Motion Design going in a lot of different directions.

Its inclusive nature, in terms of the range of styles and techniques that can be utilized, creates tremendous possibilities. We can make vector animation, kinetic type, live-action compositing, 3D, stop-motion, illustrative animation, frame-by-frame animation, etc. It is difficult to find a medium or aesthetic that can be excluded from Motion Design.

As a discipline, we have built a solid foundation that services the advertising and entertainment branding industries. Now, we are beginning to explore other facets for Motion Design, like interactivity and user experience design.

This exploration will only increase as the Internet of Things expands. I have almost completed my 2nd Masters Degree, this one in Interactive Design. I see an interesting area of research within the intersection of motion & interactivity and the duality of user & viewer. Both motion and interactivity utilize change to engage viewers and users, but in different ways and for different reasons.

I have adjusted my mental model of what it means to be a motion designer. I used to think that designers and 2D animators were a different breed than 3D artists, with the rare exception who could do it all.

Since being at SCAD, I have learned that if you teach 3D to students, as part of their foundation, in addition to design and 2D animation, they use it all! As tools for creating interactive motion become more accessible, I imagine they will also become part of the motion designer’s toolkit.

I think the future of motion design is very bright, as screens are everywhere. From the devices in our pockets to wearable tech and projection mapping, I see motion designers working across a range of industries as hubs of creativity.

Design for Motion: Fundamentals and Techniques of Motion Design now available.