TRIPLE BILL is a groundbreaking trilogy of short films using replacement animation—a technique where every frame features a unique 3D-printed puppet. This method swaps models frame-by-frame, creating hyper-detailed, fluid motion unachievable with traditional stop-motion. Each film explores a genre to showcase the medium’s atmospheric power:

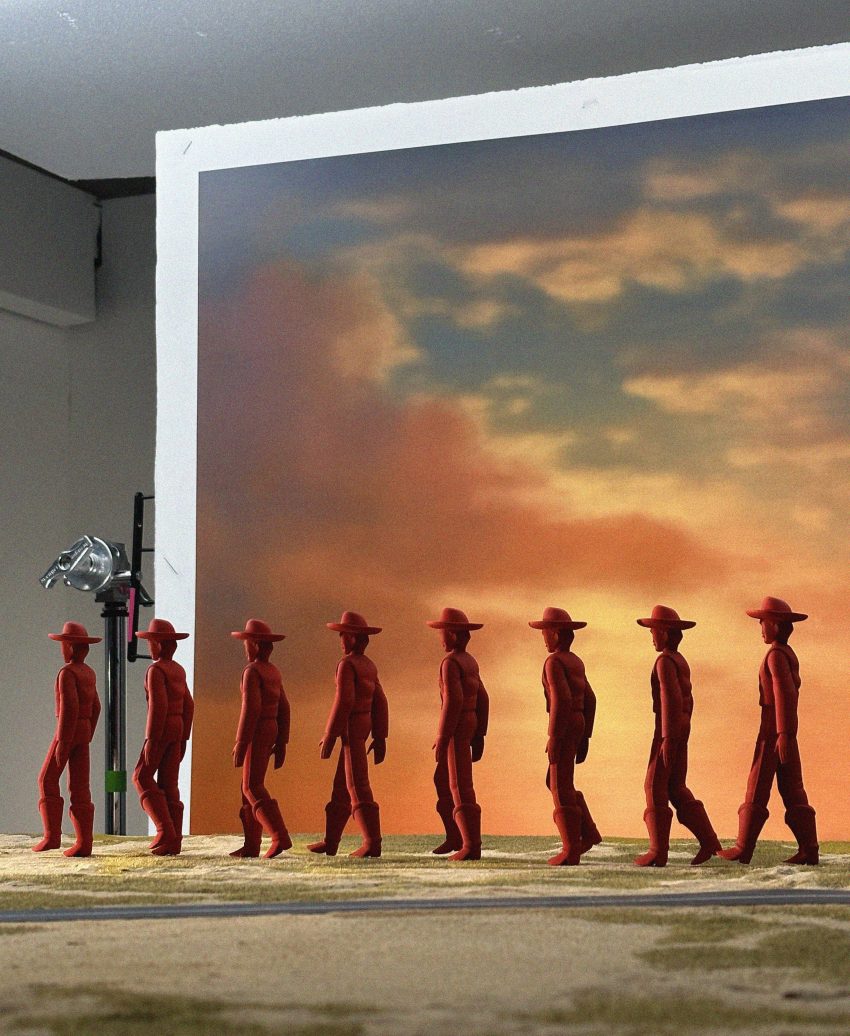

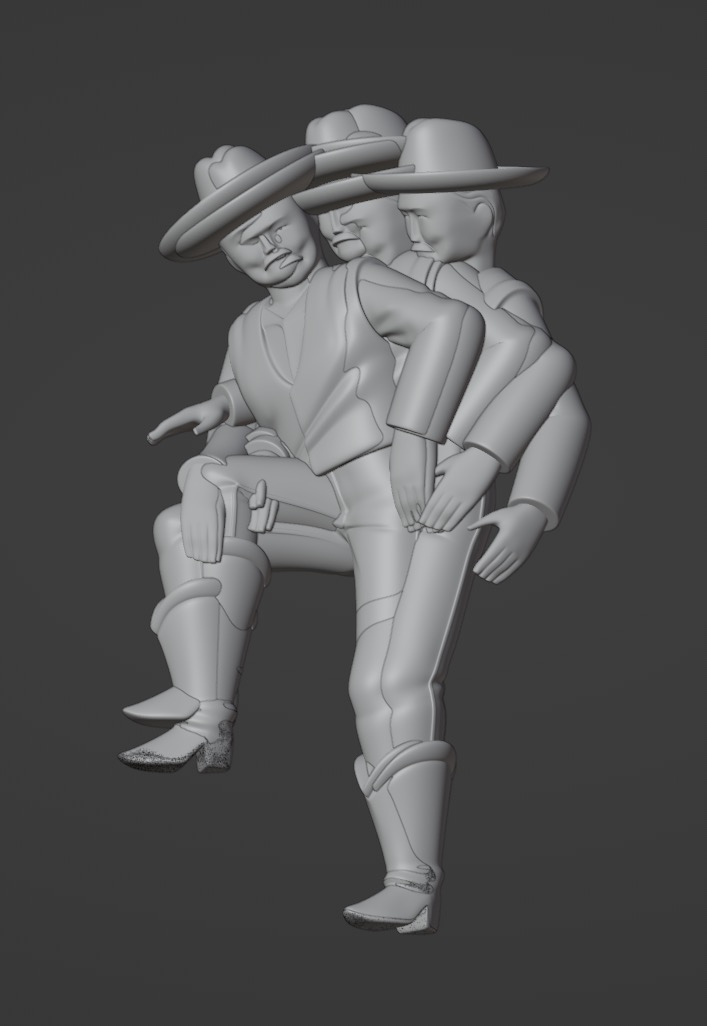

BLUE GOOSE — A western poking fun at the enshittification of our online spaces.

CLUB ROW — A film noir on data privacy featuring a hypnotic, spinning staircase.

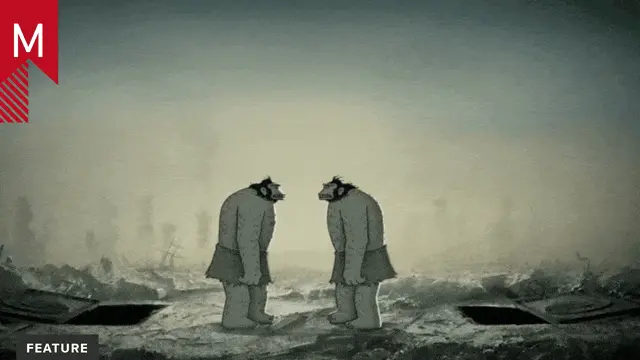

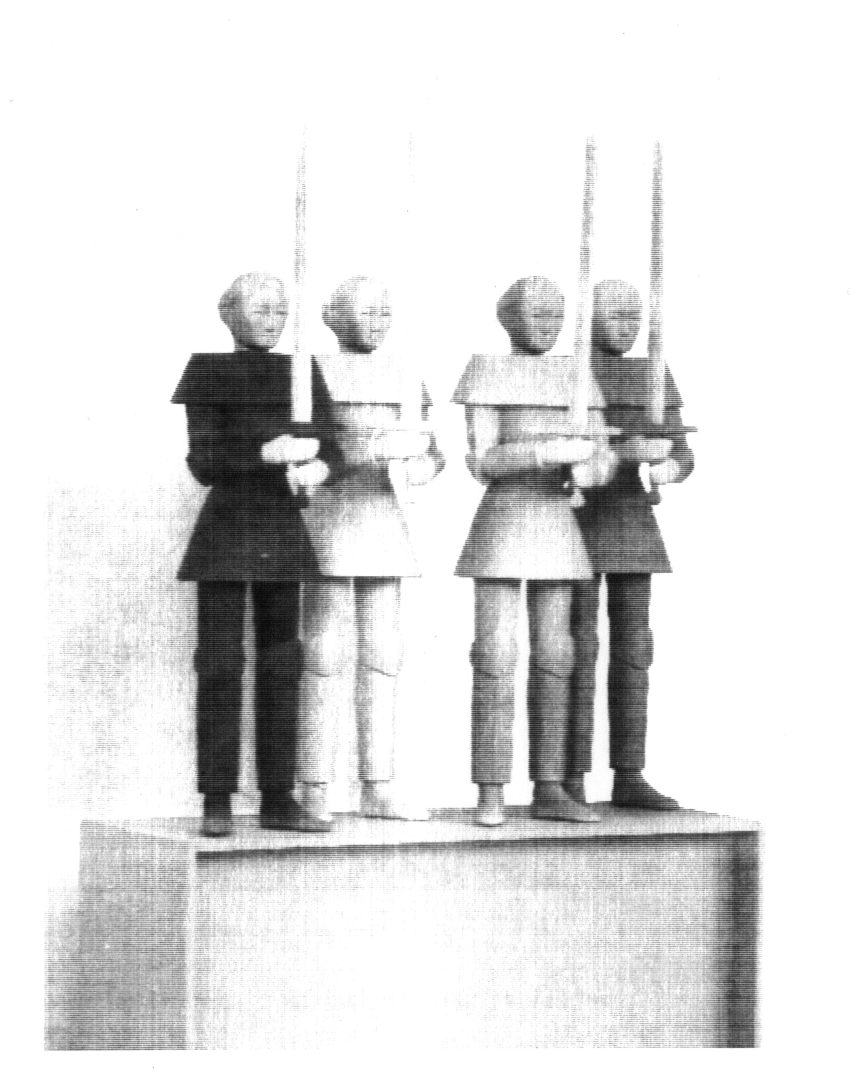

MYTHACRYLATE — A modernist fantasy for the century of the self, making use of the multiplicity of characters inherent to replacement animation.

Instead of an armatured puppet, our puppets are composed of dozens of iterations of themselves, which are “replaced” every frame. George Pal popularized the technique with wooden characters in the 1930-1940s, but we do it using 3D printing. Ie.: to solely make the cowboy walk, it takes eight models.

Eastend Western directs and produces animated films in a wide range of styles and techniques, from hand-drawn to stop motion. It is led by internationally awarded directors Jack Cunningham and Nicolas Ménard, who share a love of poetic narratives, meticulous craft, and memorable world-building. They’re represented by Nexus Studios for commercials.

Jack Cunningham & Nicolas Ménard

The Paper-First Mantra Behind 3D Animation’s New Wave

- How did TRIPLE BILL balance traditional storytelling with experimental techniques?

- What inspired the team to merge 3D printing with handcrafted animation, and how did this hybrid approach shape the workflow?

- How were narrative ideas translated into visual concepts during the early brainstorming phase?

- What collaborative challenges arose between designers, animators, and 3D printing specialists, and how were they resolved?

–

Since replacement animation can be a laborious process, each short story was conceived with the feasibility of its construction in mind. Mythacrylate, for instance, was about the re-use of a single sword-swinging action. Because it takes 18 single puppets for the motion, it’s possible to show a crowd. And so the story of a fight with the self emerged.

–

We’ve been working with replacement 3D prints for many years now. Already in 2016, Jack made a film for Triple Stitch using the same technique. Over the years we made more commercials for Corona and Airbnb at Nexus Studios, with the support of big teams. So we accumulated many ideas of how we would want to design our own world, free from commercial constraints. TRIPLE BILL tries to sum up some of those ideas, and allowed us to reverse engineer the pipeline so we can produce such films more independently.

–

We always start with small thumbnails on paper to create a rough storyboard and animatic. This allows us to quickly see if the idea holds up. If it doesn’t, it can be swiftly re-sketched and iterated. Too much software early on can get in the way of ideas!

–

For most of the project, we wore the hats of designers, animators, and 3D printers. Because of this, we kept the 3D printed result in mind through the rigging and posing process.

The Triple Bill Guide to Bridging Eras Without CGI

- How did the team establish a cohesive visual tone that nods to classic movie mood while feeling modern?

- What role did color theory play in evoking the project’s gritty, nostalgic atmosphere?

- How did sound design and music interact with the visual tone to create an immersive experience?

–

We storyboarded and sketched to achieve the clearest of intentions within each frame. Luckily for us, the project didn’t call for any elaborate camera moves, in turn opting for a very grounded camera which probably adds to the ‘classic’ movie feel.

–

We often think of colour as trying to create a memorable impression. A cowboy statue that’s fully painted red is rather bold, so it creates a lasting impression. We try not to explore too many variations which we feel can lead to a paralysis of choice. The colours often align at the start of our process with the initial idea influencing the pallet.

–

For Blue Goose, our friend Bridget Samuels came on board to craft an eerie, midi western melody that set the uneasy tone of the film. This was complemented with beautiful sound design by Joe Wilkinson who created a distinct, ship-hull like sound for our moving statue.

For Club Row, Jack used a digital synthesizer for the soundtrack, which fitted the era of the film perfectly. Then, Nicolas used the BBC symphony orchestra plugin to score Mythacrylate. Both of them took a fair bit of trial and error, but we very much enjoyed dusting off the old keyboard.

The 3D-Printed Jenga That Built a Stop-Motion Crowd

- How were 3D-printed models integrated with digital animation—scanned, manually tracked, or both?

- Did 3D printing materials (e.g., resin, PLA) impact texture, weight, or motion flexibility?

- How was stop-motion adapted for 3D-printed elements? Were rigs or armatures required?

- What role did digital compositing or VFX play in enhancing 3D-printed elements?

- Were any custom tools or software developed to streamline 3D printing and animation workflows?

- How did animators and 3D printing specialists collaborate to ensure models were structurally sound and animation-ready?

–

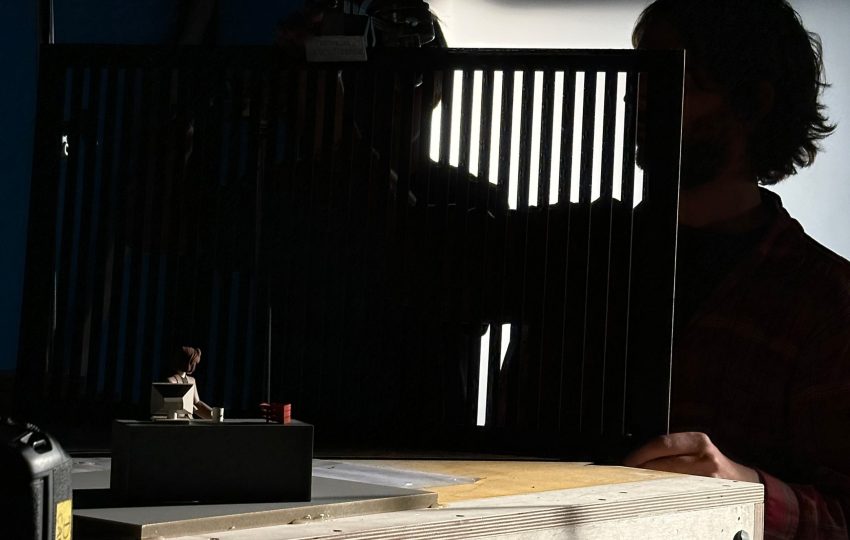

Everything was shot in camera at Arch Film Studio in East London, thanks to the kind support of long time collaborator and champion Andy Gent. There is no digital animation integration.

–

The very fine texture on the surface of the resin 3D prints adds a delicate boil to the animation. We did a lot of sanding to get as smooth a finish as possible.

–

With this technique – except if one is looking to shoot things in mid-air – no rigging is required but a pin to make the characters stand. For this reason we like to call our figures “seamless puppets”. In between printed poses, the figures were nudged slightly to smooth out the motion.

–

We did some rig removal on the spinning staircase, but otherwise the only VFX we did was a grade to make the colours more filmic. This was done beautifully by Jonny Tully at Cheat and No. 8.

–

We used Blender for the whole process and it didn’t require additional tooling.

–

As we were both animators and 3D printers, this was fairly straightforward technically, but trickier creatively.

To avoid unnecessary labour, we limit ourselves to the required poses only. After a first pass of animation in Blender, we review the motion and delete as many frames as possible to see what we can get away with. And because we reduce the amount of frames, we try to make sure every print is as good looking as possible.

PRO & CONS: Dust, Drama, and 3D Dilemmas

- Did 3D-printed models create a more emotionally resonant experience than purely digital assets?

- How were sustainability concerns, such as plastic waste, addressed?

- Is this hybrid approach viable for large-scale productions, or best suited for niche projects?

–

We think there’s something fundamentally different in a picture shot in camera – the imperfections and the intricacies of real light and dust grounds the experience in a way that’s hard to replicate digitally.

Creatively, going through this process produces all sorts of happy accidents which we couldn’t have planned. The reflections in the coffee mug of Club Row, for instance, was completely improvised on set by a bouncing light shifted frame by frame.

–

Unfortunately, the resin used for 3D prints isn’t currently recyclable, but the waste generated by support structures is minimal, especially at the small scale we work at.

–

We feel like it’s an ideal technique for short films. Feature film grade armatured puppets are very expensive to produce, while 3D printed replacements can produce more characters more cheaply.

How Rapid Prototyping is Rewriting Animation’s Rulebook

- Could 3D printing democratize motion design by lowering barriers to tactile prototyping?

- How might advancements in rapid 3D printing reshape pre-production workflows for animation studios?

- Will hybrid techniques (e.g., 3D printing + AI-generated motion) redefine the role of animators?

- What industries beyond film (e.g., gaming, advertising) could adopt 3D-printed Motion Design next?

–

3D printing is certainly more accessible today than it was 15 years ago. However, it is far from a magic button that animates automatically. It still requires a lot of specialist knowledge and time to model, animate, and process. For us, the appeal is in its precision.

–

It has already made its mark in the stop motion industry; from Laika using it for replacement faces, to its more general use in the production of props and molds.

–

There is no semi-automatic or automatic technology that can replace the pictorial quality of traditional animators’ work. New technologies will offer alternative aesthetics; in the process we can only hope we avoid too much deskilling.

–

The commercial budgets are what allowed us to experiment with 3D printing in the first place. Now that we’re establishing a language in the medium, the applications are endless. Product design is next on our agenda. As charming as it is working in miniature, the opportunity to work ‘people sized’ feels like a very exciting prospect.